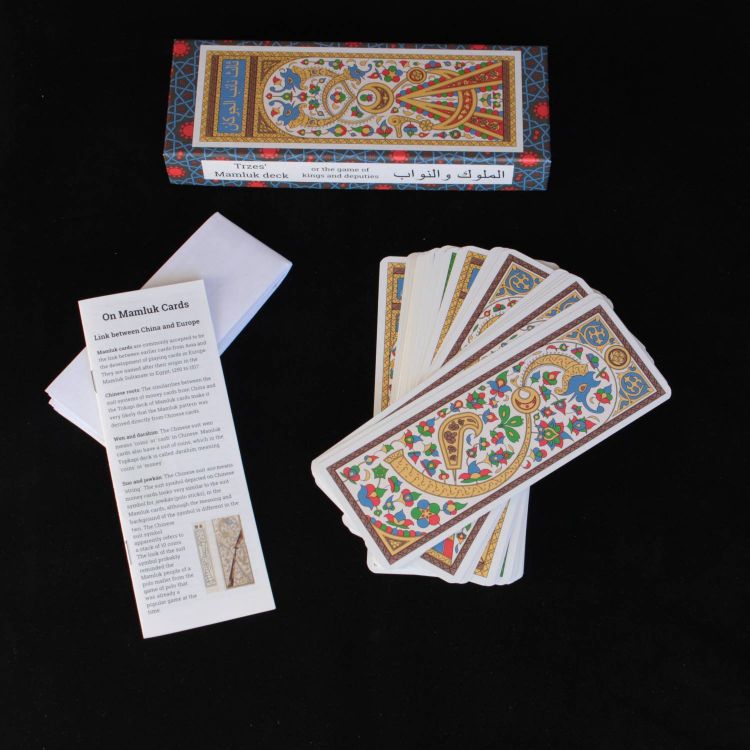

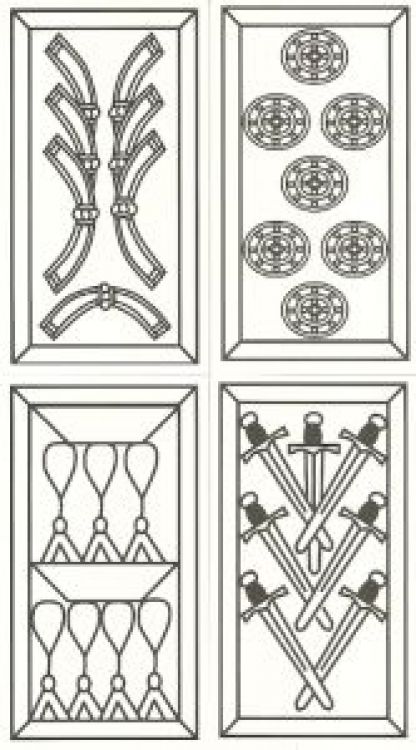

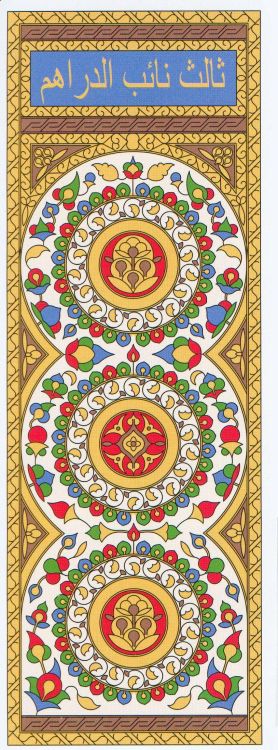

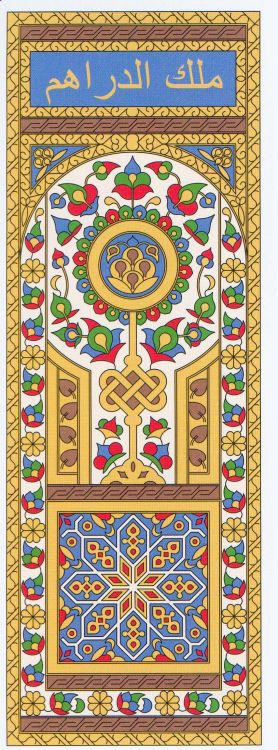

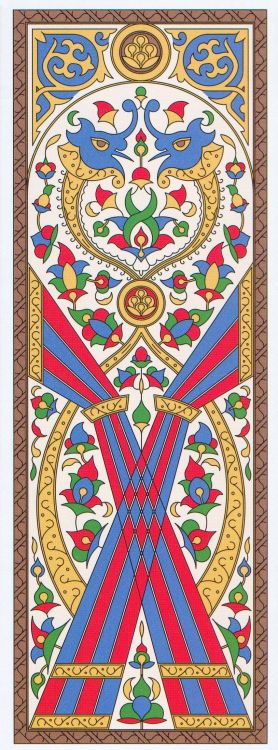

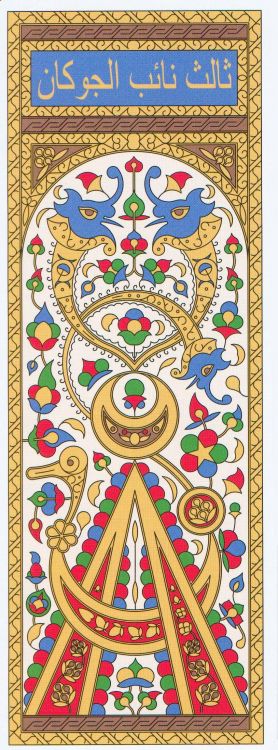

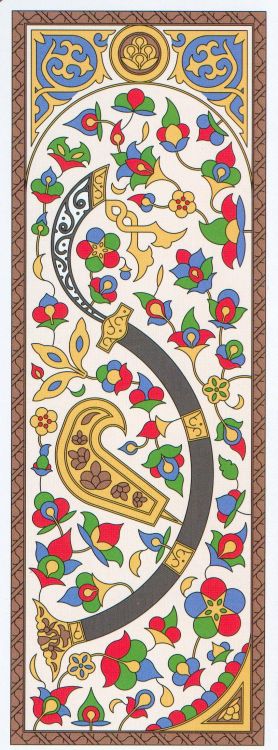

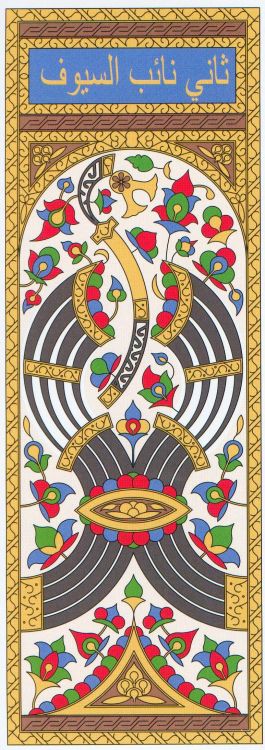

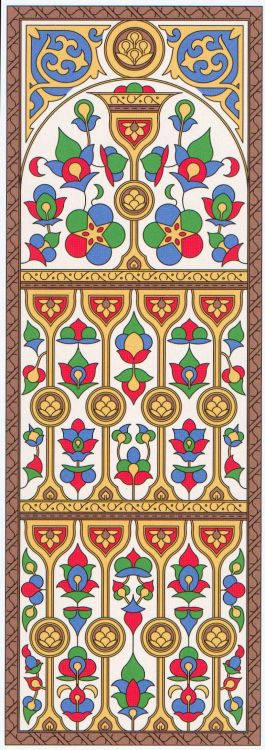

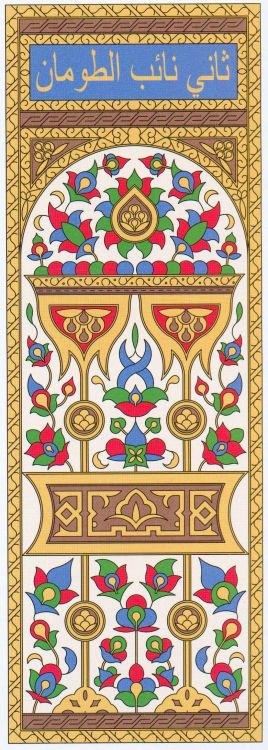

This game is a favorite. My purchase was motivated by the fact that this game has inspired all European playing cards. If the Tarot de Marseille is "the father" of the divinatory tarot cards, this game is "the father" of the playing card games. It is therefore normal to have a copy of it when one seriously studies the history of card games.

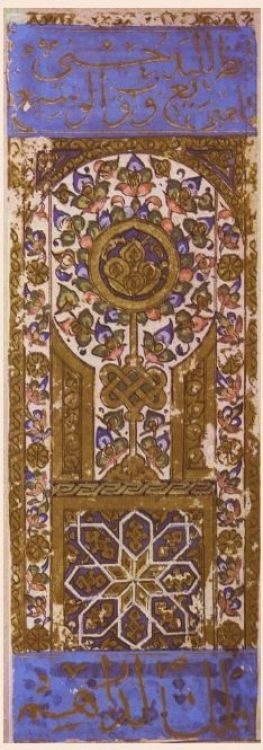

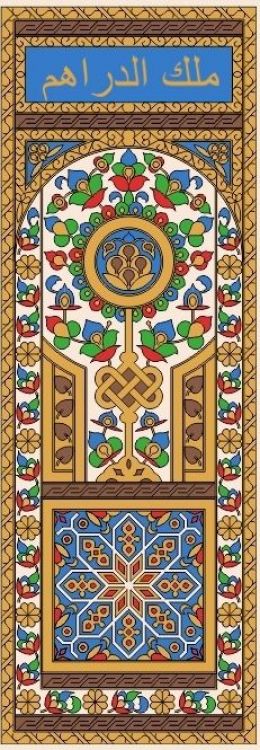

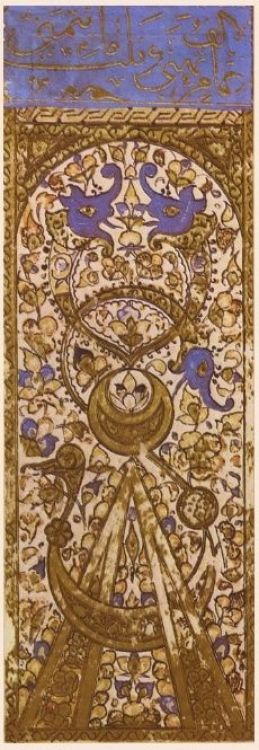

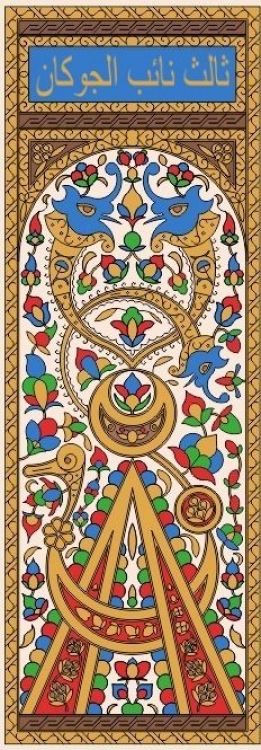

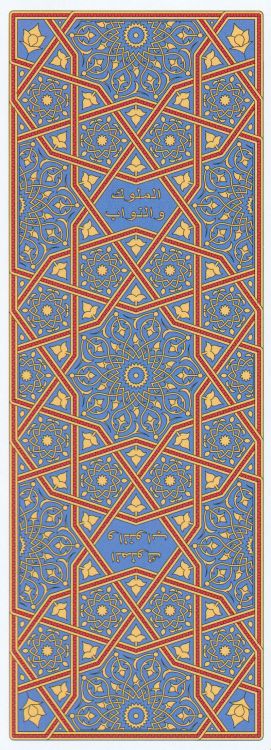

The unique and magical graphics of this game also caught my eye at first glance. As a game collector that I am, I didn't hesitate to get a copy.

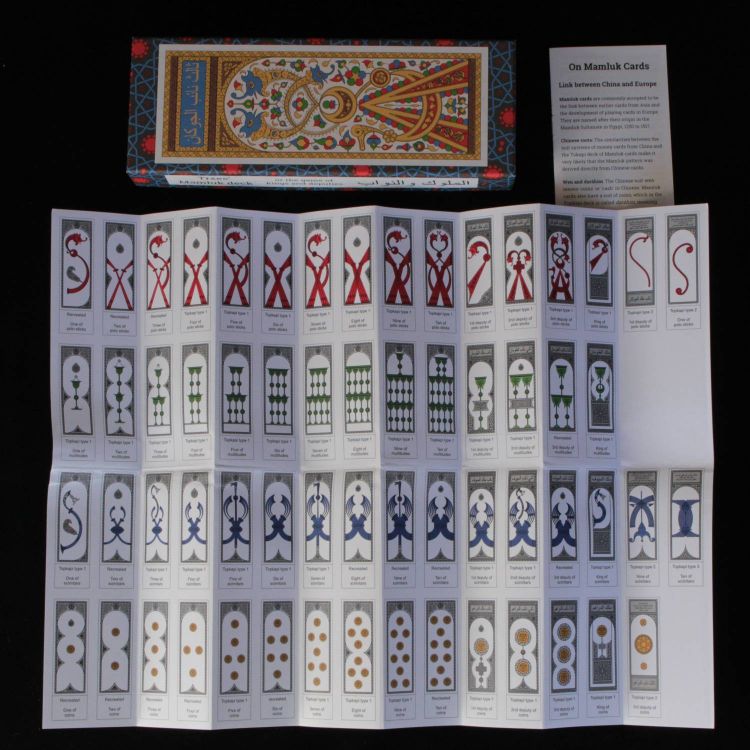

Beyond the undeniable historical interest of the game, its definite graphic beauty, it must be admitted that this game is not adapted to divinatory practice, be it predictive or psychological. The cards are very big and even too big. The Mamluk game corresponds nevertheless to a complete Minor Arcana. This is already very good, but many will regret the absence of a Major Arcana. For my part, I use this game in divination, as an exercise in developing intuition and clairvoyance, and on draws based only on the Minor Arcana. This practice would perhaps only be of interest to advanced students.