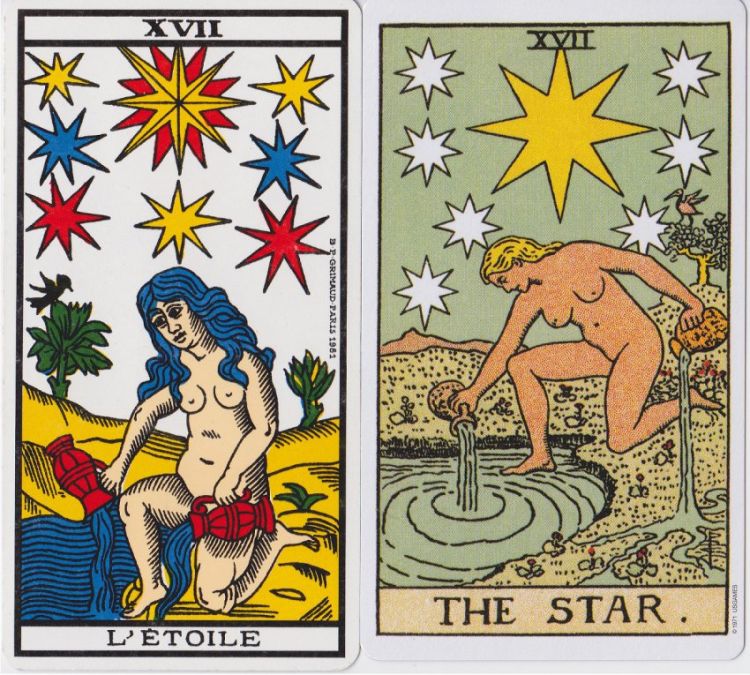

Over time, the Star card in Tarot has shown many different images. Sometimes it was Medieval astronomers, other times a naked woman pouring water into a basin. Nobody really knows what this card originally represented. Is it a Bible story? An ancient Egyptian tale? Or perhaps a zodiac sign? Experts and historians don't agree. But this ambiguity isn't a problem - it's what makes the card interesting! Since it doesn't have a single precise meaning, everyone can see different stories in it and give it their own interpretation.

The woman pouring water in the Star card most likely represents a fusion of several ancient goddesses. In Mesopotamia, the eight-pointed star was the sacred symbol of the goddess Inanna (Sumerian) or Ishtar (Akkadian), a deity associated with love, war, and the planet Venus. This goddess was later assimilated to the classical goddess Aphrodite/Venus during the Hellenistic period.

In the Egyptian tradition, similarly, the goddess Sothis was specifically associated with the star Sirius, whose heliacal rising (appearance of the star just before sunrise) in the east announced the annual flooding of the Nile, a vital phenomenon for Egyptian civilization. This figure was later assimilated to Isis in Greco-Egyptian mythology, especially during the Ptolemaic period (332-30 BCE).

The eight-pointed star has been associated with the goddess of love since Mesopotamian representations of Inanna/Ishtar on artifacts dating back to the 4th millennium BCE. But during this period, all planets were commonly represented with stars having six to twelve rays, without any systematic correlation between the planet Venus and a specifically octagonal star.

In 16th century astrological engravings, Venus generally appears accompanied by the symbols of Taurus and Libra (the zodiac signs she rules according to traditional astrology), and often topped with a six-pointed star. This variation in the number of branches raises important questions about the definitive identification of the card with the planet Venus. Especially since in classical mythological iconography, Venus/Aphrodite is rarely depicted in the act of pouring water.

The most obvious and historically documented correspondence is that established between the Star card and the astrological sign of Aquarius, the eleventh sign of the zodiac. Traditionally, Aquarius (Aquarius in Latin) is represented by a male figure pouring water from a jar, an iconography dating back to Babylonian astrologers who identified this constellation as "the Great One" or "the Water Bearer".

In medieval tradition, particularly in illuminated manuscripts and early printed almanacs of the 15th century, significant iconographic variations appear. Notably, there are female representations of Aquarius pouring water from two distinct containers. This duality in gender representation could explain the feminization of the figure in the tarot card during its codification in the 17th century.

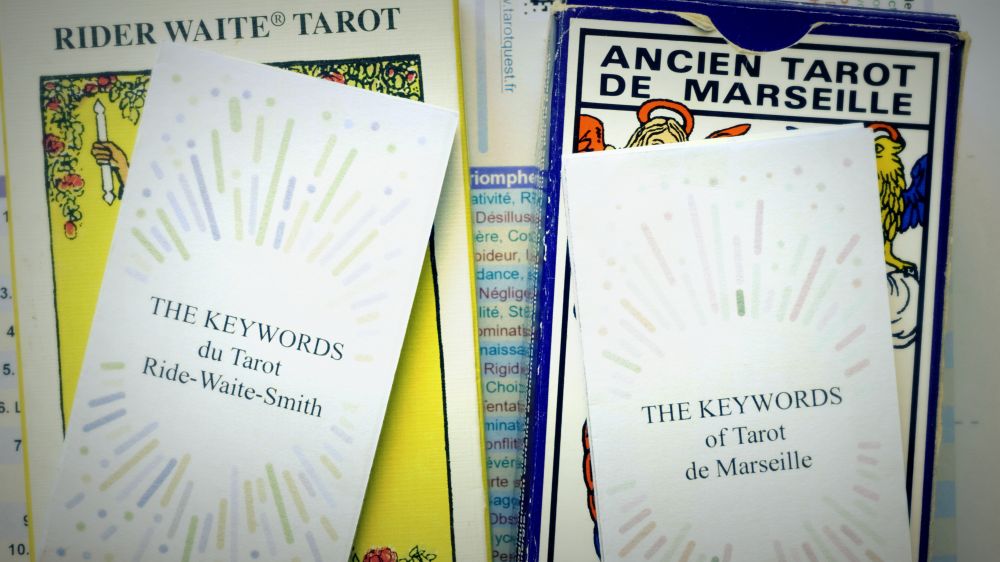

Another constellation associated with this card is the Pleiades, the star cluster visible to the naked eye in the constellation of Taurus. In Greek mythology, the Pleiades are the seven water nymphs, daughters of the titan Atlas and the oceanid Pleione. Their myth tells how the giant Orion pursued them relentlessly until Artemis, goddess of the hunt, intervened to protect them by first transforming them into seven doves, then into seven stars.

The bird perched in the tree on the Star card could be a subtle reference to their temporary transformation into doves, creating a symbolic link between heaven and earth. The eighth star, larger and central in the traditional iconography of the Marseille Tarot, would represent according to certain esoteric interpretations of the 18th century their father Atlas, a titanic figure condemned by Zeus to stand at the western edge of Gaia (Earth) to support the celestial vault on his shoulders.

This attribution nevertheless poses a significant conceptual problem: Atlas is not a star in classical mythology, but a character generally represented in Western art as a man bent under the weight of the celestial globe. This shows how tarot can be over-interpreted by mixing various mythological traditions.

Representations of naked women pouring water from two jars remain relatively rare in European art of the 15th and 16th centuries. A particularly relevant example can be found in the frescoes of Palazzo Te in Mantua, a pleasure residence built between 1525 and 1535 for Federico II Gonzaga. These frescoes, created by Giulio Romano and his workshop, present a Naiad in a posture surprisingly similar to that of our card.

Naiads, in Greek mythology, are aquatic nymphs specifically associated with springs, fountains, streams, and other freshwater sources. Daughters of Zeus according to some traditions, they personified the purity of waters and their regenerative power. During the Italian Renaissance, in the context of the rediscovery of ancient texts and Plato, these pagan figures were reintroduced into artistic iconography, especially in aristocratic residences as symbols of abundance and fertility.

This figure of the Naiad, combining femininity, nudity, and water, is part of a long symbolic tradition where poured water represents both spiritual purification and transmission of sacred knowledge.

In the Christian tradition, the quintessential guiding star is the Star of Bethlehem or Christmas Star, a celestial sign that, according to the Gospel of Matthew, announced to the Magi from the East the birth of Christ and guided them to Jerusalem and then Bethlehem. This miraculous star constitutes a powerful symbol of hope and divine guidance in Western Christian iconography. Nativity scenes and Christmas trees are traditionally adorned with a star, perpetuating this symbolism even in our contemporary traditions.

The Star of Bethlehem is also a flower as can be seen opposite. Its white flowers in the shape of a 6-pointed star appear from April to June and have the peculiarity of opening in the morning and closing in the evening, hence its common name "Eleven o'clock Lady."

The Star card in the hand-painted deck by Este, dating from the mid-15th century, presents a scene quite different from the versions we have today. This ancient version combines two themes popular during the Renaissance: characters pointing to the sky and astronomers/astrologers manipulating their measuring instruments. A particularly revealing detail is the pointed hat worn by the man on the left of the composition. This distinctive headgear was used in medieval art to signal a foreigner from the East, most likely a reference to one of the three Wise Men.

This interpretation fits perfectly within the cultural context of the Ferrara court, where the Este family, patron of the arts, cultivated a pronounced taste for Christian iconography. The star represented would thus be the Star of Bethlehem, contemplated with wonder by the Magi. This card testifies to this period of the early versions deeply rooted in Christian religious imagery.

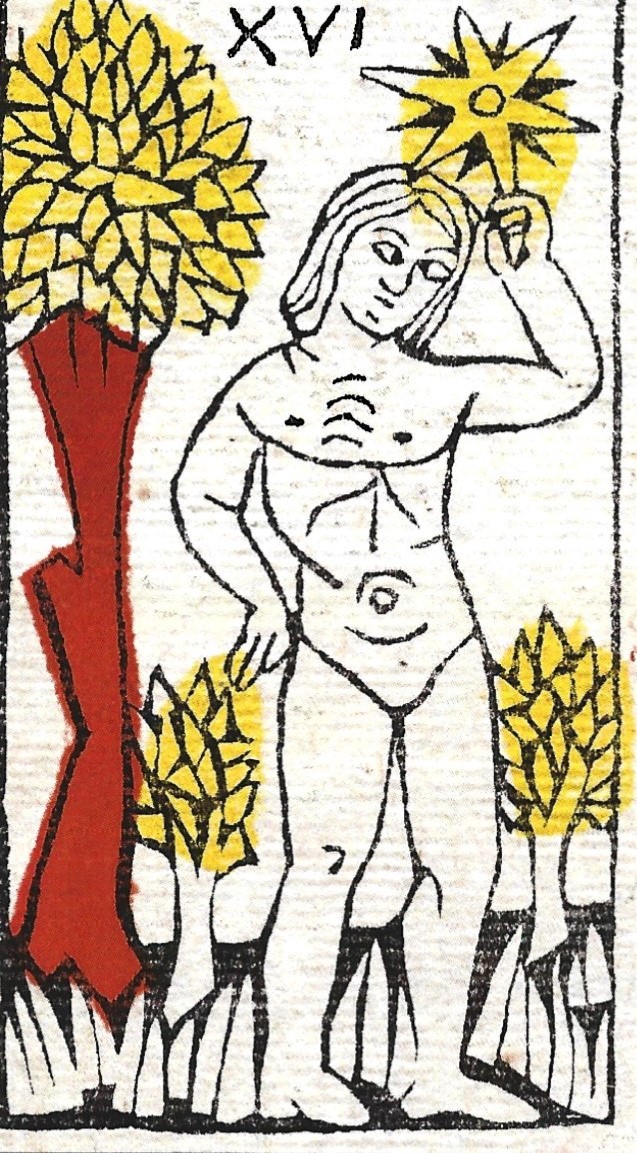

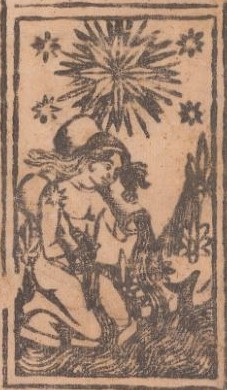

In a significant evolution, the Star card of the Visconti-Sforza tarot, a luxurious deck hand-painted for powerful Milanese families, as well as the Budapest card printed with a stamp, both present a different scene: a solitary figure extending a hand toward a star, as if to grasp it.

Unfortunately, these versions provide no contextual clues to precisely identify this character or explain their gesture. This ambiguity could be interpreted in several ways: either as a simplified representation of astronomers or magi observing the heavens, or as an illustration of an allegory or popular story of the time whose reference has been lost over the centuries. The context of the princely courts of Northern Italy, where astrology and astronomy enjoyed great intellectual prestige, nevertheless suggests a valorization of celestial knowledge and the quest for knowledge.

This transition phase testifies to the period when tarot, first an aristocratic game, began to spread more widely, requiring reproduction techniques such as stamp printing, which allowed greater production but also imposed a simplification of motifs.

The Cary Sheet is a rare document dating from around 1500, presenting an uncut sheet of tarot cards. This historical piece is particularly valuable for understanding the iconographic evolution of tarot through the centuries.

This sheet represents an essential link in the history of tarot, illustrating the transition toward the imagery found in the Tarot of Marseille.

The main innovation of this version is the appearance of a kneeling character pouring water from two pitchers into a body of water, an element that will become characteristic of later versions.

The gendered identity of this figure remains subject to debate among specialists. This ambiguity could be intentional, reflecting the hermetic currents of the time where androgyny symbolized a form of primordial perfection.

The card features an imposing eight-pointed star accompanied by four smaller stars. A notable detail is the presence of a wand or rod ending with a star held by the character, an element that will disappear in subsequent versions. This object could represent a magical attribute or a simplified astronomical instrument.

This representation marks a significant evolution: earlier versions often featured astronomers observing the sky, while here aquatic elements are added. This transformation testifies to the influence of Neoplatonic currents that associated stars with celestial influences and water with their transmission to the earthly world.

The Cary Sheet thus reveals the gradual fusion of astronomical and aquatic symbols that shaped the enduring iconography of the Star card as we know it today.

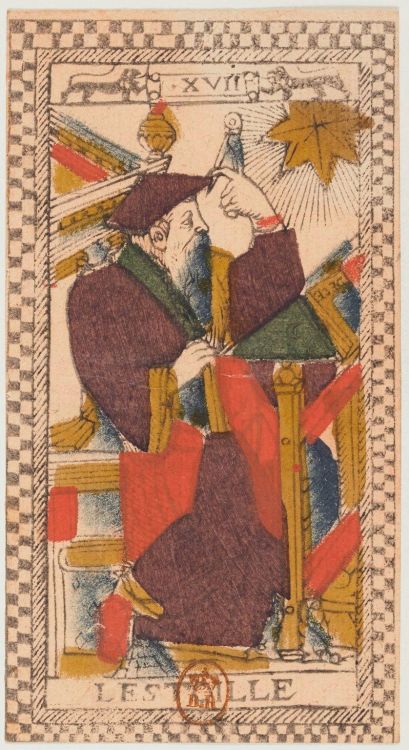

When tarot spread to France in the 16th century, the Star card underwent an unexpected change: the image of the astronomer or astrologer returned to the foreground. In the anonymous Paris Tarot, we find a scholar sitting at his desk pointing a measuring instrument called a caliper toward the sky. Similarly, the tarot created by Jacques Viéville features an astronomer seated near a tower with the same instrument.

This representation of the astronomer became the standard version of the Star in the "Rouen-Brussels" tarot model, very popular in the 17th and 18th centuries in northern France and present-day Belgium. This choice to keep the astronomer as a central figure reflects the rise of astronomical sciences during the Renaissance, a time when discoveries by Copernicus and later Galileo were profoundly transforming our vision of the universe.

An interesting element to note is that the number of rays of the main star and the number of small stars surrounding it vary greatly from one version to another. This variation is not anecdotal: it corresponds to the different ways stars were represented in astrology and astronomy works of this period. Contrary to what some modern interpretations of tarot suggest, the number of rays or stars did not have a strictly codified meaning - these variations were more related to artistic choices or technical constraints linked to engraving.

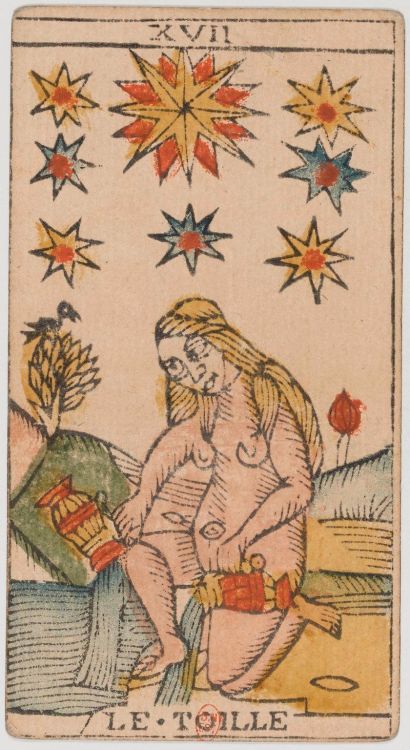

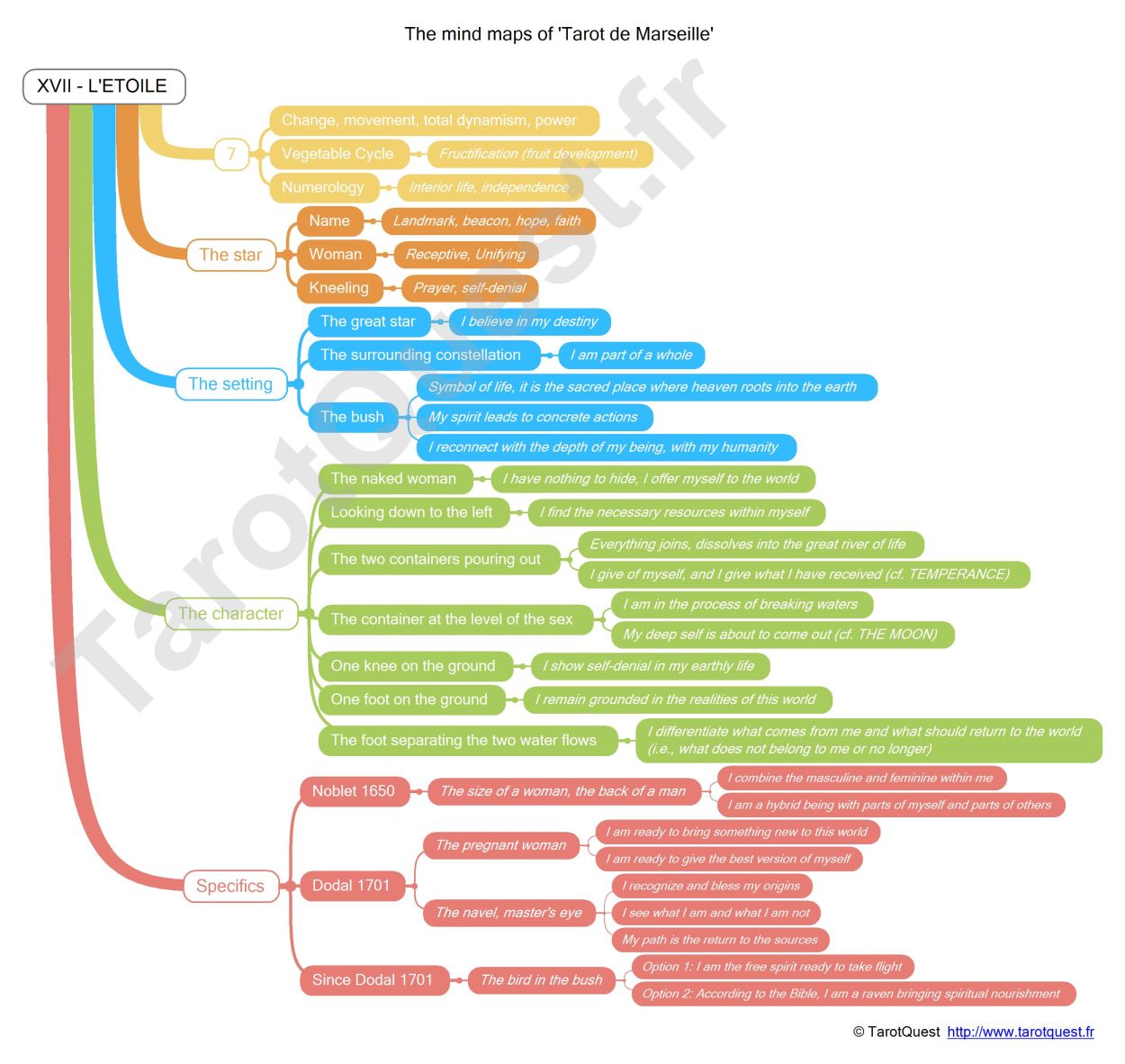

The tarot created by Jean Noblet represents a major turning point in the history of the Star card and lays the foundation for what will become its classic representation in the Marseille tradition. Although inspired by the Cary sheet, Noblet introduces decisive changes that profoundly transform the symbolism of this card.

The most striking innovation is the appearance of a clearly naked female figure, recognizable by her hair and exposed chest. She simultaneously pours from two amphorae: one into water, the other onto the earth. This dual action introduces a new cosmological dimension, perhaps suggesting the balance between elements or the alchemical principle of dissolution and coagulation.

The celestial composition is also significant: a large central star surrounded by seven smaller stars. This configuration, different from the four stars of the Cary sheet, could reference the seven planets known to ancient astronomy or the Pleiades constellation.

A fascinating aspect of this version is the ambiguous anatomy of the central character. Despite her obvious feminine attributes, Noblet drew her with an exceptionally broad back, thus creating a masculine-feminine duality. This deliberate ambiguity fits perfectly into the alchemical tradition of the primordial androgyne, a powerful symbol of spiritual completeness very present in the iconography of the 16th and 17th centuries.

An interesting symbolic detail: the right pitcher, as it pours its water, hides the female figure's genitals. This composition could evoke a woman "breaking water," establishing a connection with birth and potentially with the star of Bethlehem. This interpretation corresponds well to the religious context of the time and echoes the Judgment card that appears later in the tarot sequence.

In this version, two trees also appear in the background, elements that will become characteristic of the Marseille style. These trees may symbolize wisdom and experience, or serve as immobile guardians of the scene. Their arrangement prefigures the two towers of the next card, the Moon, thus creating a narrative continuity. Similarly, the water flowing from the woman's feet anticipates the pond present in the Moon card, reinforcing this symbolic progression.

This version created by Noblet, through its symbolic richness and internal coherence, will serve as a fundamental model for all subsequent Marseille versions, establishing a remarkably stable iconographic model through the centuries.

Jean Dodal's tarot, printed in Lyon at the beginning of the 18th century, represents a notable evolution while preserving the essence of the model established by Noblet. Dodal makes three major modifications that considerably enrich the symbolism of the Star.

The first innovation is the appearance of a black bird perched on one of the trees. This bird, probably a raven, adds a new symbolic dimension. In many European traditions, the raven was considered a messenger between worlds, associated with both prophecy and death. In Norse mythology, the ravens Hugin and Munin (Thought and Memory) were Odin's messengers, bringing him news from the world. In biblical tradition, a raven fed the prophet Elijah in the desert. This symbolic ambivalence considerably enriches the card: the black bird becomes the messenger that connects worlds, ensuring the transmission of celestial messages to the earthly world. Its presence reinforces the central theme of the card: the transmission of celestial influences to the material world.

The second important modification is the replacement of one of the trees with what appears to be a red flower, probably a rose. In Christian and alchemical iconography of the 18th century, the red rose symbolized divine love, Christ's passion, and spiritual regeneration. In the alchemical tradition contemporary to Dodal, it symbolized the reunion of opposites. This change is not trivial: it adds a dimension of rebirth that perfectly complements the aquatic symbolism already present.

The third innovation, more subtle but equally significant, concerns the anatomy of the female figure. Dodal represented her navel in a particularly accentuated way, giving it the appearance of an eye. This representation simultaneously evokes two powerful symbolisms: that of the navel, the original point of connection between mother and child, and that of the "third eye," the center of spiritual perception in many esoteric traditions. The Star figure becomes a bridge between ordinary consciousness and spiritual perception, between physical incarnation and transcendent vision.

The evolution of the Star card reveals a fascinating transformation: what was initially a scholar observing the stars gradually became a mythical female figure pouring water. This radical change reflects profound transformations in European culture between the 15th and 18th centuries.

A particularly revealing aspect of the card's evolution concerns the number and arrangement of stars. The variation in the number of rays and the quantity of celestial bodies represented offer valuable clues about the cultural influences at work.

In the primitive versions, the number of stars was variable and was more a matter of artistic considerations than symbolic ones. In medieval and Renaissance astronomical treatises, planets and stars were generally represented with a number of rays ranging from six to twelve, without any particular consistency. This suggests that initially, the precise number of rays had no specific symbolic meaning.

The gradual stabilization toward a large eight-pointed star surrounded by seven smaller ones in the Marseille tradition marks the emergence of a more precise symbolic codification. The number eight, associated with eternity and regeneration (as evidenced by the octagonal shape of many Christian baptisteries), and the number seven, referring to the seven planets of ancient astronomy, the seven days of the week, or the seven alchemical metals, are part of well-established symbolic numerical systems in Western culture.

Antoine Court de Gébelin (1725-1784) theorized in "Le Monde primitif" (1781) an Egyptian origin of tarot. Despite its historical inaccuracy, his theory influenced the interpretation of the Star, which he associated with Isis-Sirius, whose heliacal rising announced the flooding of the Nile, thus linking the water-pouring figure to a symbolism of divine fertility.

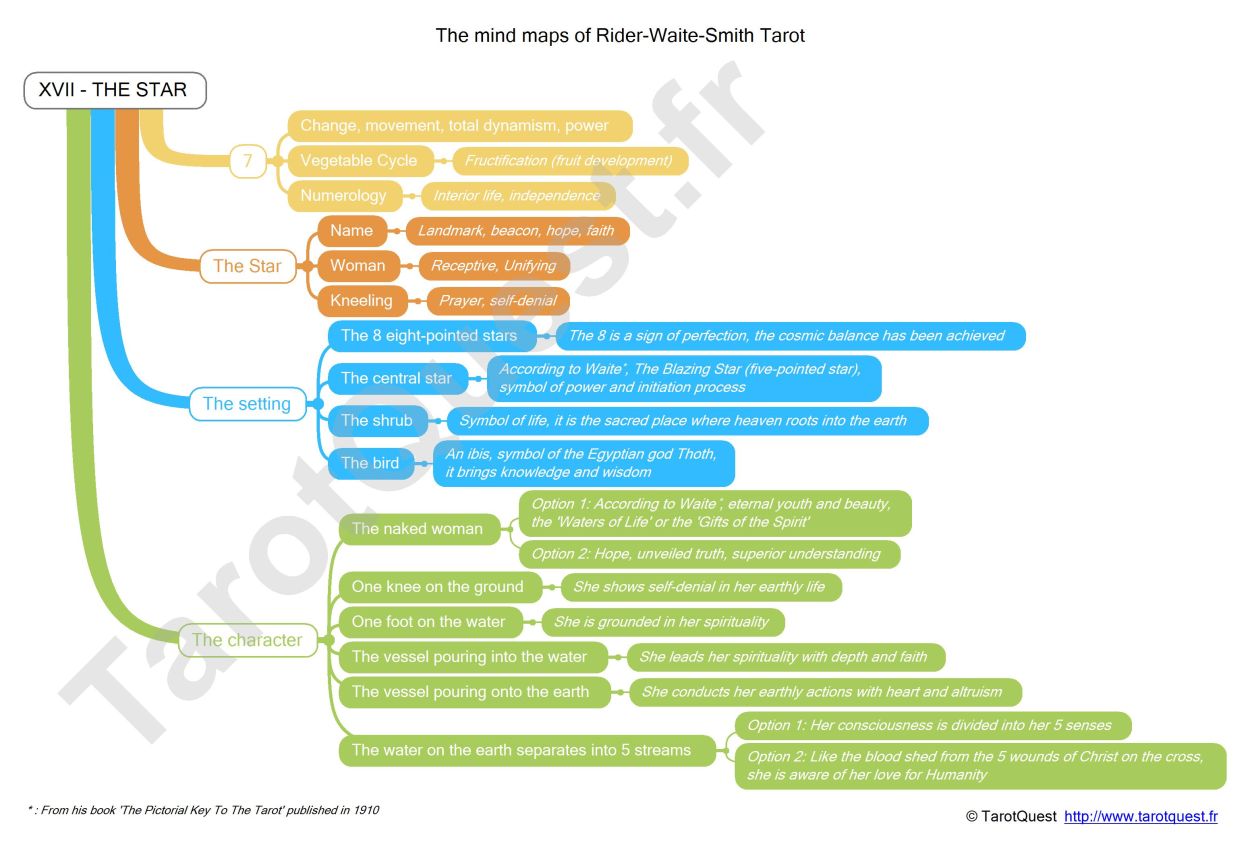

Etteilla (1738-1791) modified the traditional iconography, sometimes renaming the card "The Stars" and depicting a woman contemplating the sky. He associated it with astrology, celestial influences on human destiny, and saw it as a symbol of hope and divine inspiration.

Éliphas Lévi (1810-1875) revolutionized the interpretation of tarot by integrating it with Hebrew Kabbalah, establishing correspondences between the 22 major arcana and the 22 Hebrew letters. He associated the Star with the letter Phe (פ), connecting it to Mercury and concepts of communication. For him, the bird in the Marseille version became a celestial messenger, and the woman embodied the transformed soul pouring the water of spiritual knowledge. The two pitchers represented the universal duality whose reconciliation was necessary for spiritual fulfillment.

Oswald Wirth (1860-1943), a Swiss Freemason, revolutionized tarot imagery with his "Tarot of the Medieval Imagemakers" (1927). His version of the Star introduced several important symbolic innovations: he replaced the traditional bird with a butterfly representing Psyche (the immortal soul transformed after trials) and associated it with a rose, evoking the myth of Eros and Psyche as an allegory of the union between the human soul and divine Love.

Wirth also added an acacia branch, a Masonic symbol of immortality and spiritual rebirth. In his alchemical vision, the liquids poured by the woman had a precise meaning: from the golden vessel sprang an ardent liquid (active/sulfuric principle) revitalizing stagnant water, while from the silver vessel flowed pure water (passive/mercurial principle) nourishing nature - representing the necessary combination of complementary principles in the alchemical work.

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, contrary to Lévi, associated the Star with the Hebrew letter Tzaddi (צ) and the sign of Aquarius, reinforcing the link between the water-pouring figure and the archetype of the celestial Water Bearer. In their system, the card was named "The Daughter of the Firmament" and represented with seven-pointed stars, symbolizing the seven traditional planets. The Golden Dawn considered this card as a guide for meditation and connection to inner wisdom after spiritual upheavals.

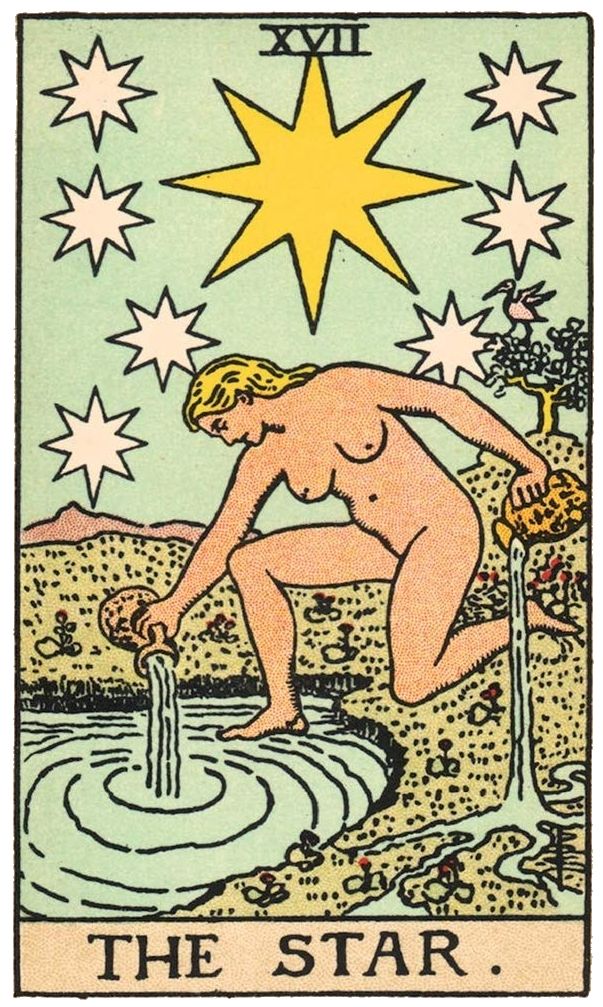

Arthur Edward Waite, influenced by Christian mysticism, saw tarot as a system of spiritual symbolism rather than a simple divinatory tool. In his version of the Star, he returned to the eight-pointed stars of the French tradition and introduced an ibis (sacred bird of the Egyptian god Thoth) perched on an acacia (tree symbolizing resurrection in the Masonic tradition). Waite interpreted the woman of the Star as representing both "eternal beauty" and the kabbalistic Great Mother of Binah, reflecting his desire to synthesize various esoteric traditions into a coherent vision.

In the Animal Totem Tarot, the Star card is completely reimagined. Instead of showing a woman pouring water, it features a large lighthouse on rocks by the sea. This change offers a new perspective while maintaining the idea of being guided and illuminated.

The lighthouse becomes an "earthly star" - it is built by humans but fulfills the role of stars: guiding in darkness, signaling dangers, and showing the way to safety. As the Star card comes after The Tower (which represents upheavals), the lighthouse suggests that after a difficult period, a light guides you to safety. Its elevated position also reminds us that sometimes we need to step back to better see our path.

The most fascinating element is a rock covered with shells, with only one open to reveal a precious pearl. This pearl, surrounded by nine bright stars, symbolizes the discovery of our inner wealth. The pearl forms when a grain of sand is slowly transformed into something precious - just like us when we go through trials. The open shell among others still closed suggests a moment of personal revelation that arrives when we are ready.

The marine environment replaces the traditional landscape and invites us to explore our deep emotions. It's unclear whether the tide is high or low, which perfectly reflects this moment of transition after a crisis but before full clarity. The numerous shells represent different possibilities opening to us - each could contain a pearl, but we must be patient to discover them.

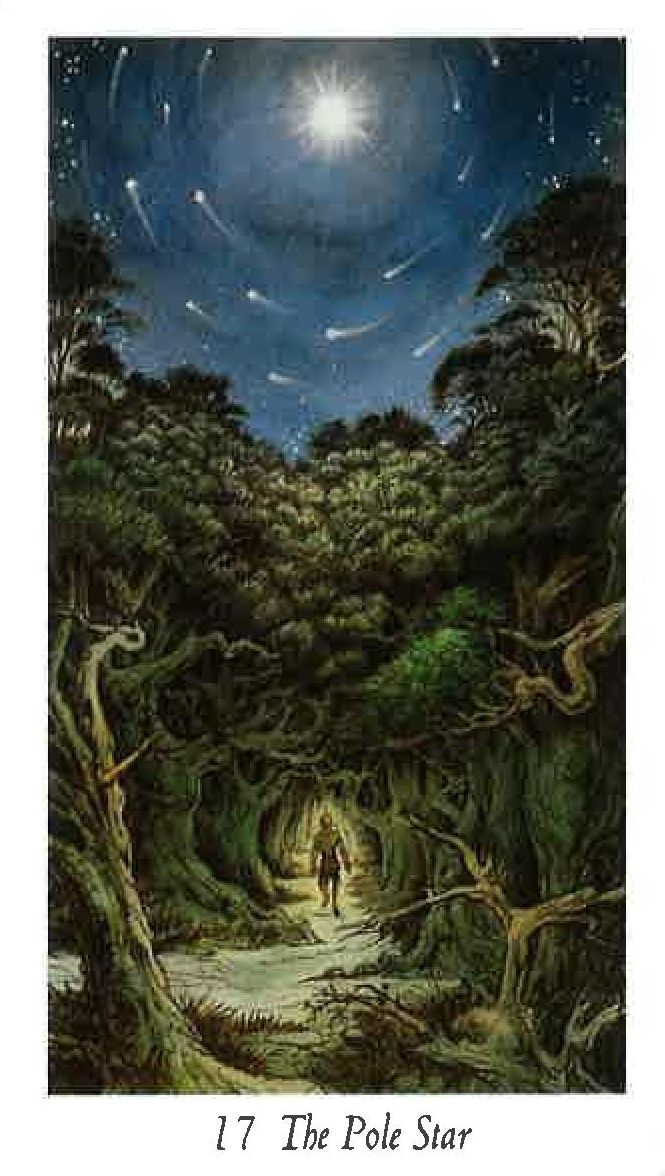

The Wildwood Tarot, created in 2011 by Mark Ryan and John Matthews with illustrations by Will Worthington, completely reinvents the traditional "Star" card. Renamed "The Pole Star," this version moves away from classic symbols to draw inspiration from ancient European traditions and the cycle of nature.

The card shows a night sky where the Pole Star shines in the center, surrounded by luminous circles formed by the trails of other stars. This image resembles a long-exposure photograph of the night sky. This is not just an artistic choice - the Pole Star has always been a reliable guide for travelers because, unlike other stars, it remains fixed in the sky. For millennia, it has represented an unchanging landmark, a constant truth amid change.

Under this orderly sky, we discover a dense, dark forest that seems almost impenetrable. This forest symbolizes the complexities of our life, with its challenges and obstacles. In the traditions that inspire this tarot, the forest is not just a physical place but a space of transformation where one can get lost before finding oneself again.

In the middle of this forest runs a path, and on this path is a human silhouette. It's not clearly distinguishable whether it's a man or a woman, nor whether this person is entering or leaving the forest. What matters is that this figure is placed exactly under the Pole Star, creating a direct connection between the celestial guide and the earthly traveler.

This card speaks to our own experience: life can be dense and confusing like a dark forest, and it is often difficult to find one's way. But like the traveler on the card, we have constant reference points - represented by the Pole Star - that can guide us even in the darkest moments. The card suggests that despite the apparent chaos of our existence, there are immutable truths to which we can align ourselves to find our direction.

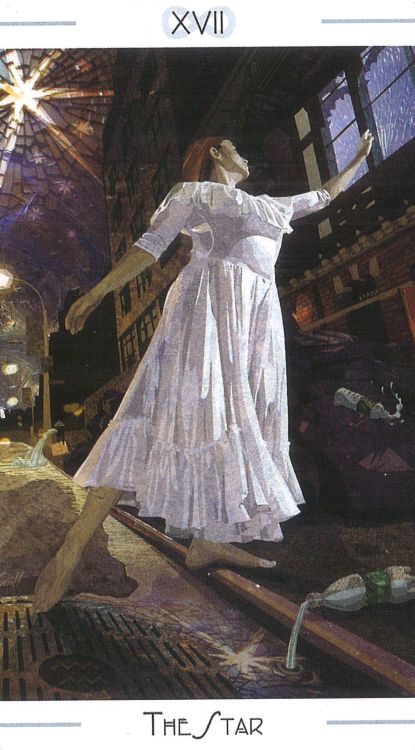

The Urban Tarot, created by artist Robin Scott in 2016 after eight years of work, transposes the ancient symbols of tarot into our contemporary world. His version of the Star card is particularly interesting because it preserves the essence of the message of hope and guidance while adapting it to our urban environment.

In this card, we see a woman in a white dress balancing on one foot, like a ballerina - a visual pun that echoes the name of the card. She is photographed from a low angle, which makes her appear taller and invites us to look up to her, as to a source of inspiration.

Water, an essential element of the traditional card, is represented in a modern way: an overturned plastic bottle pouring out its contents and an open fire hydrant projecting water into the gutter. These two water sources flow toward a drain, suggesting that even in our concrete world, natural cycles continue to exist in other forms.

The night sky is depicted as an immense stained-glass window illuminated by a bright star. The other "stars" are actually urban streetlights that illuminate the night. This mixture of natural and artificial elements reminds us that in our modern cities, where light pollution often prevents us from seeing real stars, we create our own sources of light to guide us.

Perhaps the most fascinating detail is the lit window toward which the woman extends her arm. Inside this apartment, we can see a midnight blue ceiling dotted with stars - as if the real starry sky were inside the building rather than above it. This powerful contrast suggests that our true guide, our "star," may be within ourselves rather than outside.

This urban version of the Star speaks directly to our contemporary lives. It reminds us that even surrounded by concrete and asphalt, disconnected from nature and often overwhelmed with information, we can still find inner guidance. The precarious posture of the dancer symbolizes the constant effort we must make to maintain this spiritual balance in a world that doesn't always facilitate it.

Key words for the 78 cards for the Tarot of Marseille and the Rider-Waite-Smith, to slip into your favorite deck. Your leaflets always with you, at hand, to guide you in your readings. Thanks to them, your interpretations gain in richness and subtlety.

The Star card occupies a special place in the tarot journey. It appears just after The Tower, which represents a collapse or a major crisis. The Star is not so much a card of hope as a card of new direction and reconnection with oneself.

After experiencing the collapse of our illusions in The Tower, the Star shows us the moment when we begin to rebuild ourselves with more authenticity. It's a necessary step before exploring the deeper and hidden parts of ourselves (symbolized by the next card, The Moon).

The two pitchers held by the woman on the card aren't simply pouring water - they can be seen as pouring tears. These tears are important and healing. They come when we recognize our past mistakes (XV - The Devil) and represent a necessary emotional release (after The Tower). These flowing tears will symbolically form the lake we'll find in The Moon card - our emotions create the space where we can explore our unconscious.

The woman's nakedness on the card is significant. It represents our return to authenticity, the abandonment of masks and pretenses. After the destruction of our ego in The Tower, we find ourselves vulnerable but true. This nakedness symbolizes humility and transparency with ourselves, essential qualities for our personal growth.

Contrary to common belief, the Star doesn't so much symbolize hope as a clear vision of the path ahead. It represents that moment when we finally understand what's truly important in our lives, after having lost our usual reference points.

We can draw an enlightening parallel between the Temperance card and the Star. In Temperance, the angel pours water from one pitcher to another, keeping everything in circulation but losing nothing. It's the image of "give and take" - I give but I also expect something in return. In the Star, the woman pours water from both pitchers at the same time, keeping nothing for herself. It's the image of a more evolved love, one that gives without expecting anything in return.

The Star shows us that after abandoning our ego and our false ideas about ourselves, we can rediscover who we truly are. It's this return to our authenticity that will give us the strength to then explore our shadow areas and our fears (in XVIII - The Moon).

This card teaches us that true love consists of giving freely, without calculating what we'll receive in return. It also shows us that tears and vulnerability, far from being weaknesses, are strengths that help us reconnect with our inner truth and prepare our future growth.

| Symbolic interpretation | Right direction (Positive) | Compassion, altruism, hope, direction, ideal, vocation, fraternity, cohesion, imagination, art, aesthetics, purity, landmark, good star, luck, protection | Reverse direction (Negative) | Despair, daydreaming, gullibility, unrealistic, vulnerability, loss, disappointment, bad luck |

| Psychological interpretation | Right direction (Positive) | Inspired, inventive, altruistic, optimistic, generous, kind, authentic, sincere, candid, sensitive | Reverse direction (Negative) | Carefree, dreamer, conservative, fearful, suspicious, discouraged, ignorant, agnostic |

| Advice | |

| Do not lose hope. Have faith and trust in yourself and others. Seek the truth. Be moral in your heart. Follow your intuition. Your star will guide you | |

| Thematic Interpretation | Love | Ideal love. Spiritual or romantic relationship. Confusion between kindness and love. Love by proxy. Illusory or one-sided feeling | Work | Artistic inspiration. Involvement in a promising project. Human enterprise. Social work. Loss of motivation. Search for a vocation. Humanitarian work. Volunteering | Money | Money is not/no longer a problem. Unexpected external contribution. Disappointing remuneration. Vain work. | Family / Friendships | Brotherly friendship. United family. Cohesion. Diverging goals. Disappointed expectations | Health | Good health. Rest and well-being. Optimism in recovery (or not). New spirituality. Fear of the future. |

| Divination / Prediction | Who ? | A visionary person. An inventor. A philosopher. A spiritual guide. A muse. A homeless person. A lost or desperate individual. | Where ? | A library. A laboratory. A study office. An art workshop. A music studio. A church. Their room | When ? | An innovative or collective project. A conference. Good news. A starry night. A candlelit dinner | How ? | By working with others. By doing a 'good deed'. By believing in their star. By praying. By writing a poem. By confiding in their diary |

Copyright © TarotQuest.fr