The Hanged Man in the Tarot de Marseille may seem enigmatic and puzzling. However, if we had lived in an Italian city during the Renaissance, we would have been more familiar with such representations, which were commonly posted on city center walls at that time. As with many tarot images, we just need to look at 15th-century Italian popular culture to better understand this card.

The pittura infamanti literally means "paintings of shame" in Italian. These works were displayed in public spaces of Italian cities during the Renaissance. They depicted men hanged by one foot, considered traitors, but who could not be executed due to insufficient legal proof. To compensate for this legal impotence, they were painted and displayed in effigy on the walls of public buildings.

These images did not survive time, as they were exposed to the elements. Everything we know about them today comes from a few preparatory sketches made with chalk by Andrea del Sarto and an ink drawing found in a book by Filippino Lippi. These two Florentine artists were major figures in Italian painting between the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

The pittura infamanti were generally commissioned by the rulers of Italian city-states to take revenge on those who had betrayed them. The best artists of the time were asked to create recognizable portraits of the traitors, suspended by one foot, accompanied by a legend specifying their crime.

In Florence, the Medici family—the richest in Europe—commissioned many paintings of shame. Their political dominance naturally provoked jealousy and periodic rebellions. When they managed to crush an uprising, they would then hire Florence’s best artists to immortalize their enemies in effigy.

Among the renowned artists who created such paintings was Andrea del Castagno, whose infamous works earned him the nickname Andrea degli Impiccati (“Andrea of the Hanged”). The famous Sandro Botticelli was also recruited by Lorenzo de’ Medici, known as Lorenzo the Magnificent, in 1478. He notably created paintings of shame depicting members of the Pazzi family, who were involved in an assassination attempt against Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano.

Even popes used these infamy paintings. For example, Pope Pius II harbored deep hatred towards Sigismondo Malatesta, lord of Rimini. He went so far as to symbolically condemn him to eternal damnation and had an infamy painting made depicting him. This painting was placed on a Roman bridge, accompanied by a banner stating:

“I am Sigismondo Malatesta, son of Pandolfo, king of traitors, dangerous to God and men, condemned to eternal fire by the vote of the Holy Senate.”

Another famous case involves Muzio Attendolo Sforza, father of Francesco Sforza, future Duke of Milan. This nobleman and condottiero, leader of a mercenary army, was renowned for numerous military victories. In 1409, he engaged his army in the service of Pope Gregory XII in the war between the Papal States and the Kingdom of Naples. However, the pope delayed paying the warlord’s fees, prompting Sforza to switch sides—a common practice among mercenaries of the time. Furious at this betrayal, the pope ordered an infamy painting with this inscription:

“I am Sforza, peasant from Cotignola and traitor. I have betrayed the Church twelve times, dishonored myself, broken my promises, my treaties, and my pacts.”

Here, it seems that the number twelve is linked to the Hanged Man, or perhaps to the twelfth card of the tarot. It can also be noted that Judas was the twelfth disciple. This number was undoubtedly chosen for its symbolic value.

What should be emphasized is that, generally, shame paintings depicted the victim, that is, the traitor, as a person writhing in agony.

Yet, on the tarot card, the character is hanged by the foot, displaying an appearance of serenity and great detachment. The tarot image may have been softened to avoid shocking. The depiction of a dying man could have disturbed and heightened the atmosphere of the cards.

Moreover, in religious paintings, martyred saints often maintain a serene expression because they have transcended human condition. For example, Saint Peter Martyr appears completely unshaken and not at all affected by the scimitar that is embedded in his skull. Religious tradition and the depiction of martyred saints may thus have paved the way for the creation of the Hanged Man's iconography, emphasizing the notion of spiritual triumph over suffering.

Another possible origin of the Hanged Man card in the Tarot de Marseille could be found in Norse mythology, through the story of Odin, the principal god of the Scandinavian pantheon. According to mythological accounts, Odin hung himself from the Yggdrasil tree for nine days and nine nights. This voluntary sacrifice aimed to acquire the knowledge of runes and gain more magical powers.

This ordeal is considered an initiatory rite, similar to those practiced by shamans in Ireland or Northern Asia. By depriving himself of water and food, Odin undergoes a ritual death that allows him to access the supreme knowledge of runes, a sacred language used to communicate with the otherworld.

It is interesting to note that this myth influenced various artistic representations, particularly among the Anglo-Saxons of the early Middle Ages, where Odin is sometimes associated with Christ on the cross. This comparison is based on the idea of voluntary sacrifice for a greater good, a notion also found in the symbolism of the Hanged Man in tarot.

This parallel between Odin and the Hanged Man illustrates a spiritual vision of sacrifice, where temporary suffering leads to an elevation of the soul and an inner transformation.

In some versions of Italian tarot, the Hanged Man card depicts a man hanging by one foot, holding a bag in each hand. This image recalls the biblical figure of Judas Iscariot, the disciple who betrayed Christ for thirty pieces of silver.

This iconographic element has often been interpreted as a reference to Judas, particularly due to the association between betrayal, guilt, and punishment. However, other interpretations are possible:

In the context of tarot decks commissioned by Italian aristocrats, this image of the Hanged Man could be an allegory of opportunistic behavior and the punishment of greed.

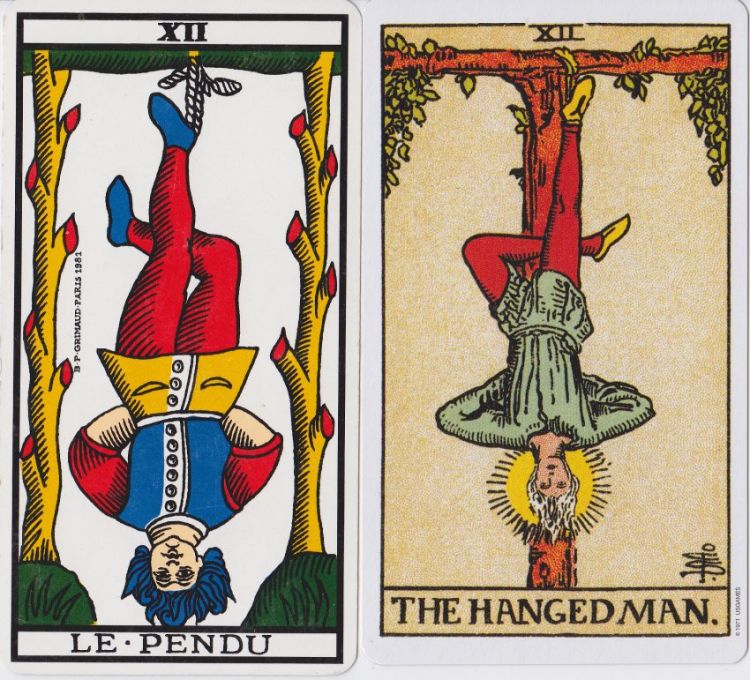

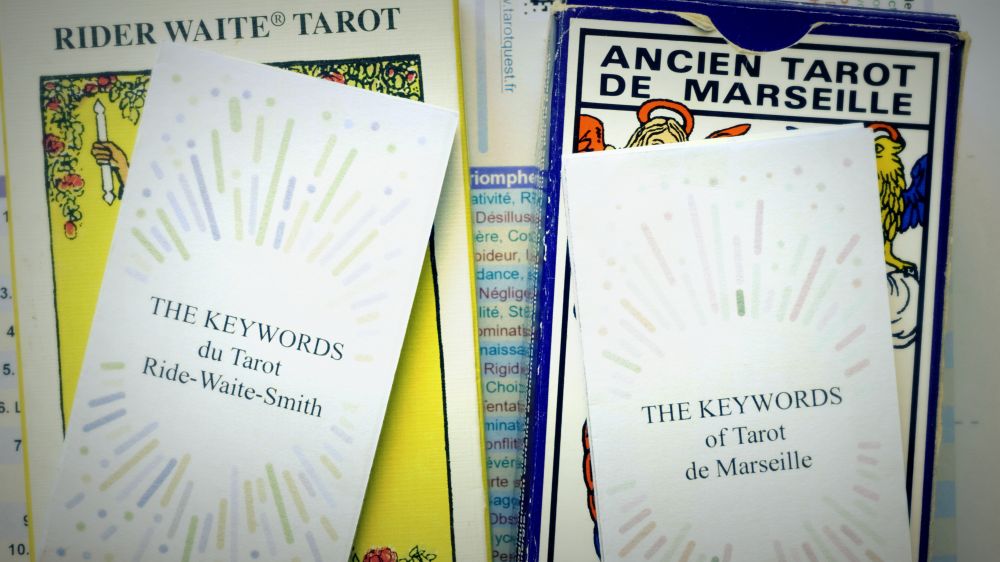

In the Visconti-Sforza tarot, the depiction of the Hanged Man stands out with its aristocratic appearance. The hanged man wears noble clothing and appears to have his hands tied behind his back. However, he shows no signs of agony; his face is instead calm and serene. This could suggest a less negative interpretation of the card, focused on resignation or a form of initiatory trial.

In the Charles VI tarot, the Hanged Man is depicted holding bags that seem to be filled with money. This detail is reinforced by the visible presence of gold coins escaping from the bags or about to fall. This imagery supports the theory that the card could symbolize the punishment of an individual who has abused wealth or betrayed for money.

In conclusion, the Hanged Man card in the early versions of tarot oscillates between different interpretations: betrayal, punishment, voluntary renunciation, or even spiritual trial. These historical representations have nourished the modern symbolism of this Trump.

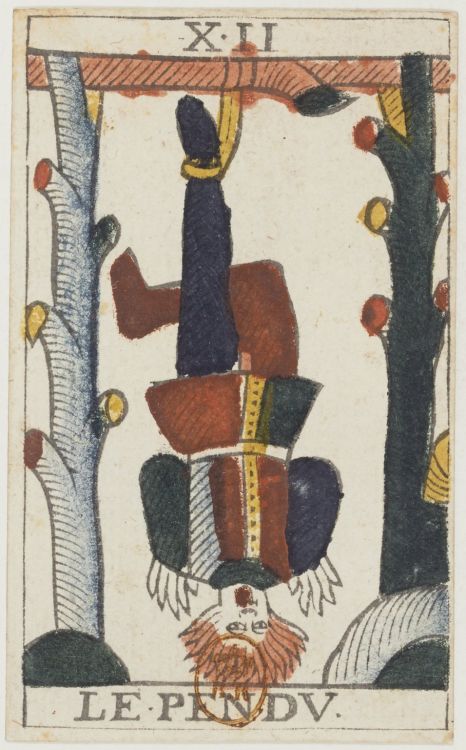

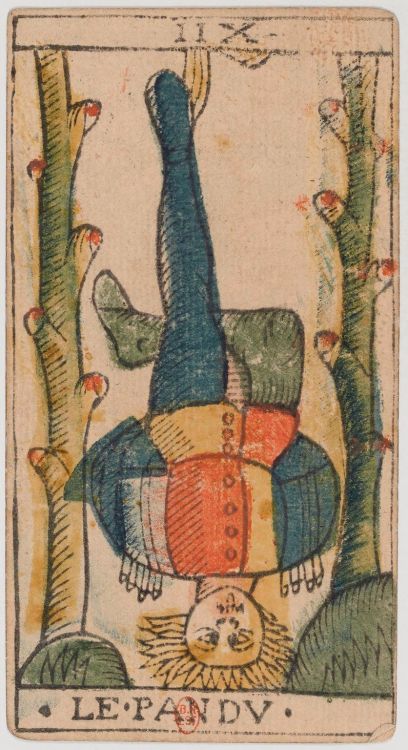

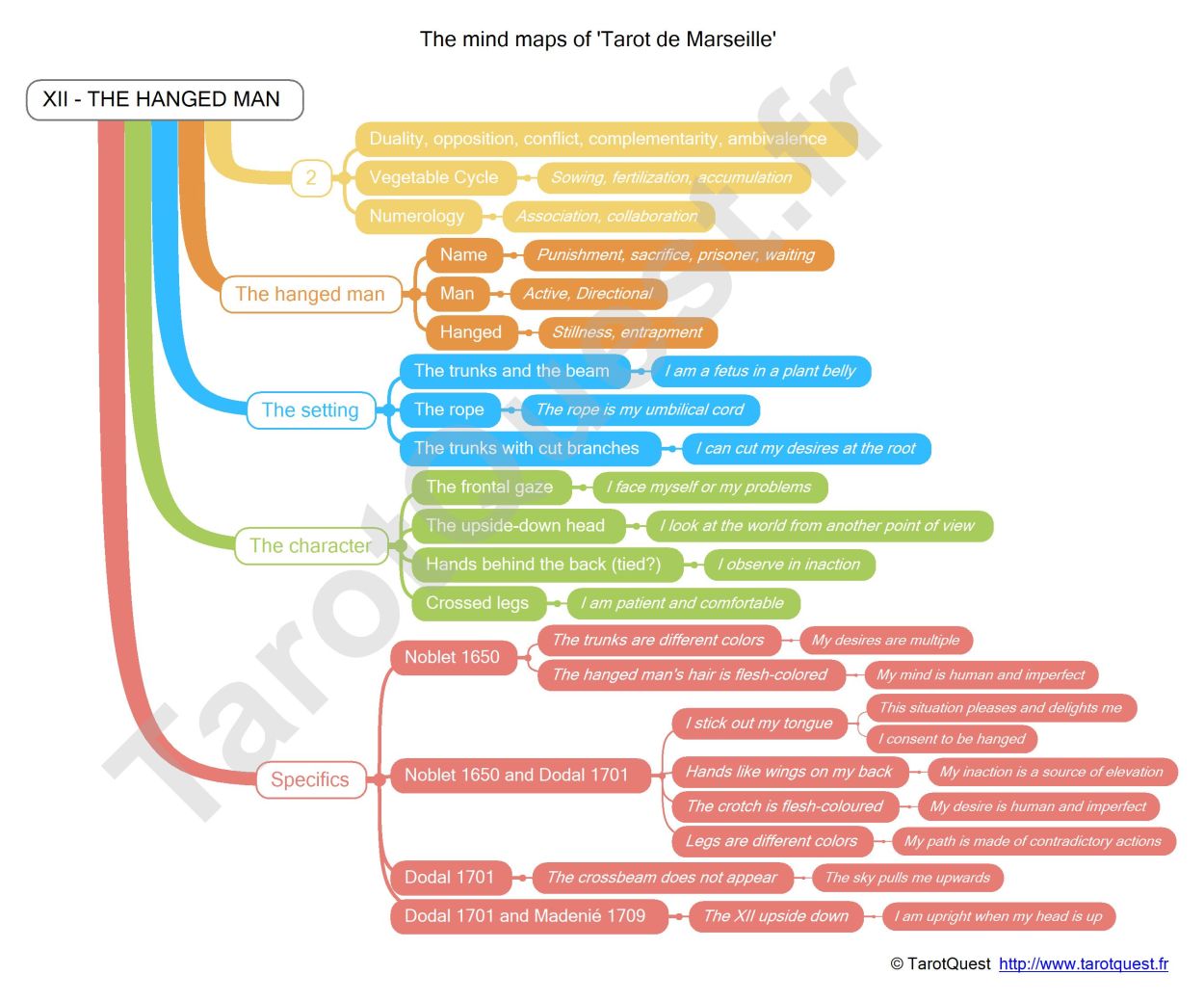

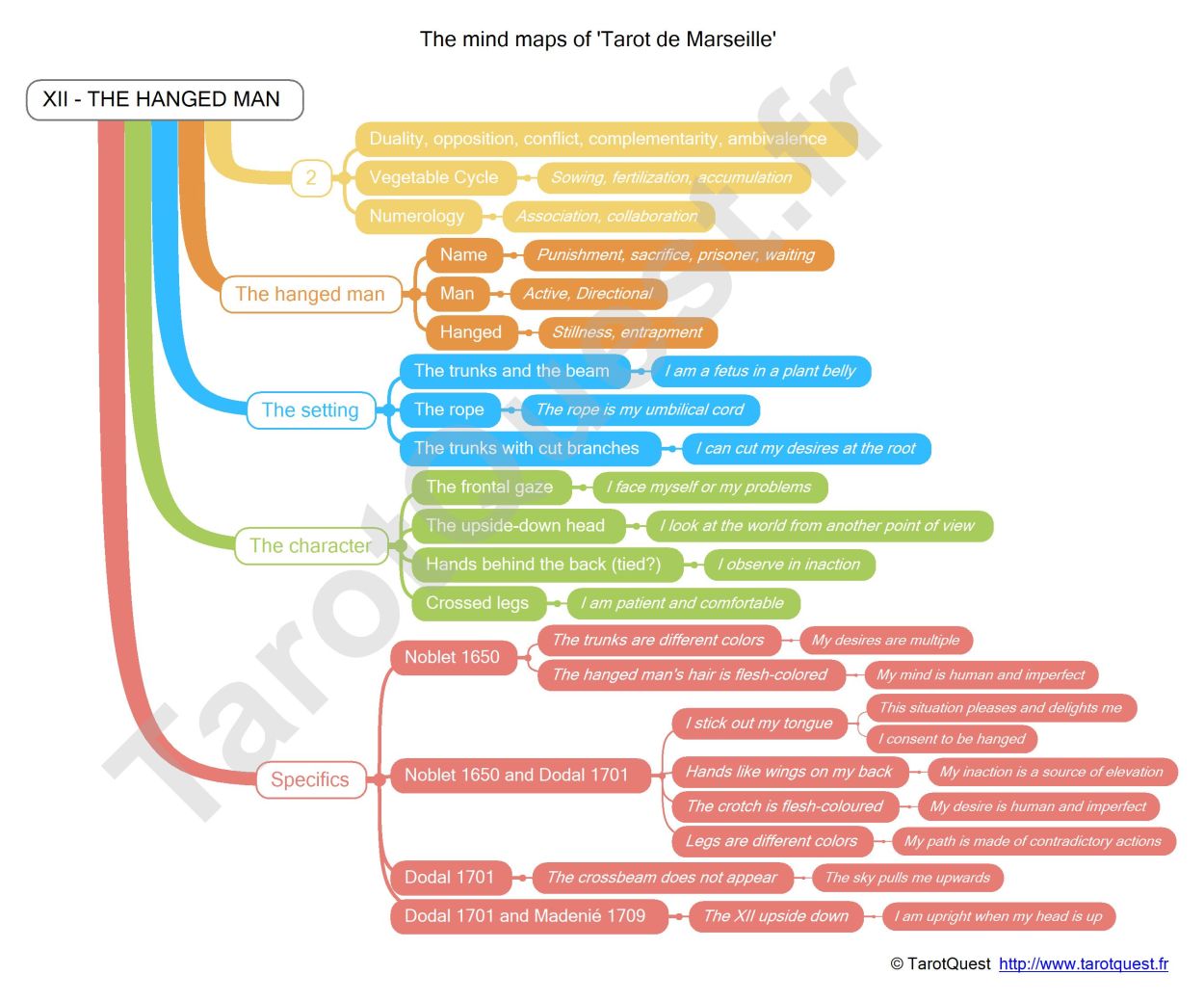

Two elements mark the early versions of the Tarot of Marseille Type I, whether it is Jean Noblet's or Jean Dodal's.

First, the man has shapes behind him that resemble tied hands behind his back. But these shapes can also be interpreted as wings. This feature gives the card a strong symbolic dimension:

This dual interpretation can be seen as a suspended or hindered spiritual awakening, where liberation does not depend on physical ability (like wings) but on awareness and inner detachment.

The second characteristic element of the Tarot of Marseille Type I is the Hanged Man’s expression. Unlike the darker depictions of the Italian Renaissance, where hanged men were often shown agonizing in the Pittura Infamanti (see above), the man here seems to be in a voluntary posture:

We are thus far from an image of punishment or torment. This version of the Hanged Man presents a more symbolic and spiritual approach to suspension, where sacrifice can be a chosen transformation rather than an imposed suffering.

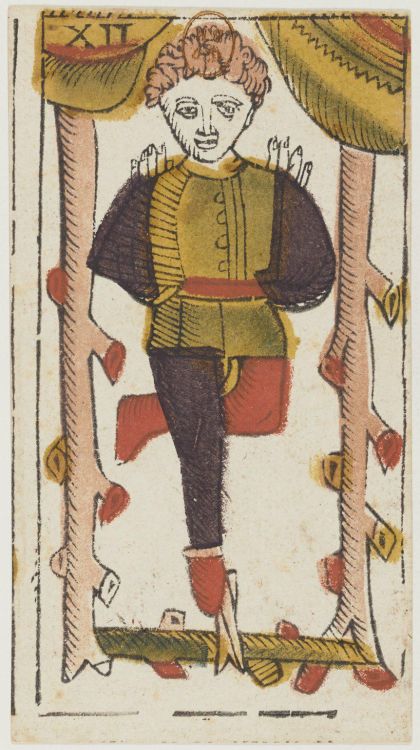

Jean Dodal brings an interesting particularity compared to Jean Noblet. A seemingly minor but significant detail: he reverses the inscription of the number XII in the card’s cartouche. Instead of reading XII, one discovers IIX. This means that to correctly read the number 12, one must turn the card upside down. Thus, the Hanged Man no longer appears with his head down but with his head upright. This inversion is a bold and subversive proposal from the master craftsman Dodal.

This characteristic originates from Viéville's tarot of 1650, which already introduced this feature. Viéville’s tarot is a precursor French tarot deck to the Besançon tarots, known for its iconographic particularities that differ from the classic Tarot of Marseille standard.

This inversion, which forces the reader to turn the card to correctly read its number, suggests a different approach to the Hanged Man. The idea that the card must be turned to be understood may resonate with the central message of this arcana: a change of perspective is often necessary to grasp the truth.

Another particularity of Dodal's tarot is the Hanged Man’s tunic. His clothing is distinguished by a vest divided into quadrants of symmetrical colors. These alternating shades could represent a balance between different aspects of the self.

By finding his center among these fundamental aspects, Dodal’s Hanged Man thus embodies a quest for awakening and inner alignment.

With Type II, two emblematic additions from Type I tarot are lost: The Hanged Man no longer sticks out his tongue, and his hands no longer form wings behind his back. These elements, which gave the character a more mystical and playful dimension, disappear in this more standardized version.

This evolution can be seen as a loss of symbolic richness. The smile and the tongue of the Type I Hanged Man suggested a voluntary stance in the face of trials, while the wing-like hands evoked the possibility of spiritual elevation. Their disappearance in Type II marks a more sober and rigid direction in the symbolism of this card.

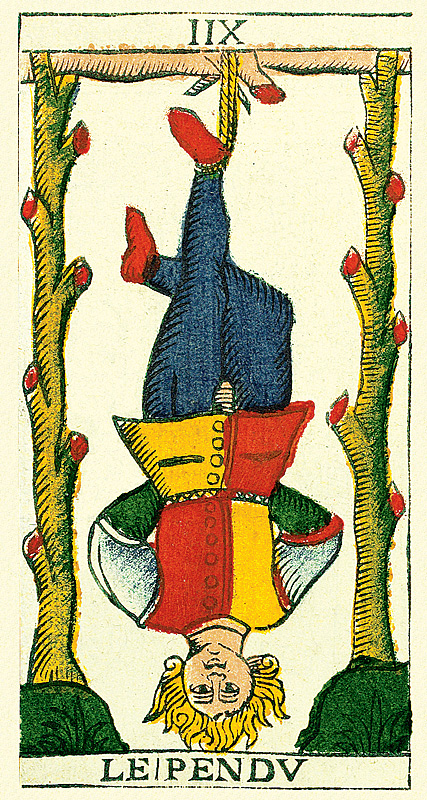

However, one interesting element remains. Pierre Madenié retains a peculiarity introduced by Jacques Viéville: the number XII is reversed.

In the Vandenborre tarot (1762), we find a compromise between the two previous types. The master craftsman of this version keeps the inversion of the number XII, thus maintaining the idea of a reversed reading of the card.

But most importantly, he reintroduces the hands behind the back forming wings. This shows that while the Type II Tarot of Marseille removed some symbols from Type I, these elements did not completely disappear: they were taken up and spread in other later versions, especially outside France.

This transmission of motifs from one deck to another illustrates the living nature of the Tarot of Marseille, where each variation tells a story of evolution in the perception and interpretation of the Trumps.

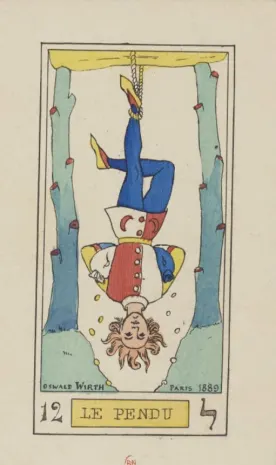

The French occultists Antoine Court de Gébelin and Jean-Baptiste Alliette (alias Etteilla in the 18th century), as well as Oswald Wirth a century later, presented The Hanged Man as a spiritual seeker reaching a turning point on his life path. The Major Arcana from 1 to 11 describe an active life, the experience of our own power, and the learning of self-mastery, culminating with the card of Strength.

With The Hanged Man, values are reversed: he surrenders to a higher power, leaves the past behind, reorients his thinking around a new set of values, and radically changes his life direction. He transcends the human condition: his body is powerless, but his soul is free and radiates great spiritual power. It is not gold coins that fall from the blue and white sacks hidden under The Hanged Man’s arms, but spiritual and intellectual treasures that he shares with the world.

The vertical poles in the design recall the pillars of the High Priestess. The blue of religious devotion fades into green, symbolizing the evolution from dogmatic religion to a freer and more living spirituality. The red and white tunic indicates that The Hanged Man is practicing self-surrender while allowing himself to be guided by his intuition. The two red buttons on his tunic echo The Emperor, indicating that he renounces his personal will to follow a higher order.

The waxing and waning moons on his pockets symbolize both the mystic’s active renunciation and his intuitive ability to receive revelations.

French occultists assigned the Hebrew letter Lamed to this card, meaning "extended arm," symbolizing an expansive movement toward the world. According to this view, divine law spreads through the world by sacred revelation: those who follow this law are elevated, while those who transgress it are punished. This aligns with earlier interpretations of The Hanged Man, often associated with punishment, betrayal, or chastisement.

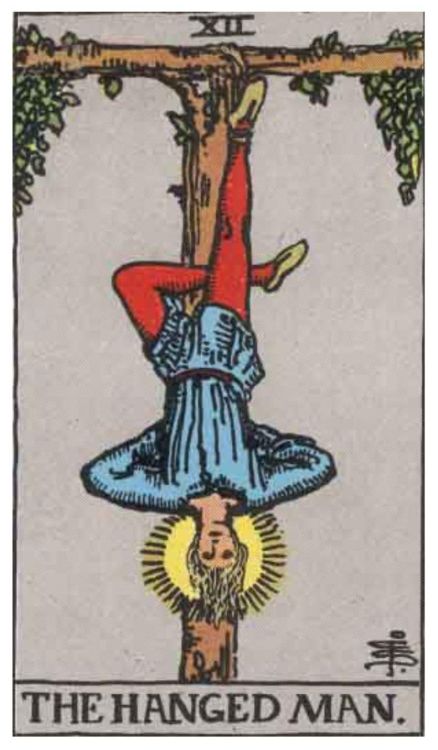

Arthur Edward Waite, in his reinterpretation of the Tarot, rejected this punitive reading and associated The Hanged Man with the Hebrew letter Mem, symbolizing water, Neptune, and Pisces. This association reinforces the idea of ego dissolution and surrender to a higher force. Waite opposed Éliphas Lévi, who attributed the virtue of Prudence to The Hanged Man, and insisted that this card does not signify suffering or punishment, but a mystical suspension.

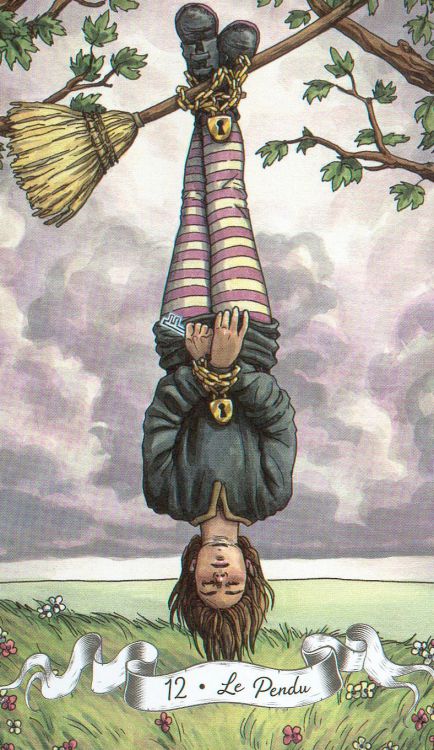

In this tarot, inspired by the symbolism of witches, The Hanged Man is represented by a young witch hanging from a tree. However, the branch to which her feet are attached is actually a witch’s broom, adding a dimension of hope and potential freedom.

Unlike classic representations, her feet and hands are not tied with ropes but with golden chains locked by a padlock. In her hands, she holds a glowing key, suggesting that she could free herself at any moment.

Her stoic expression and closed eyes show an acceptance of her state. This detail differs from traditional depictions of The Hanged Man, where the face is often peaceful but the hands remain hidden behind the back. Here, The Hanged Man literally holds the key to her own liberation, reinforcing a more contemporary interpretation of the card: the choice of sacrifice and the realization of personal power.

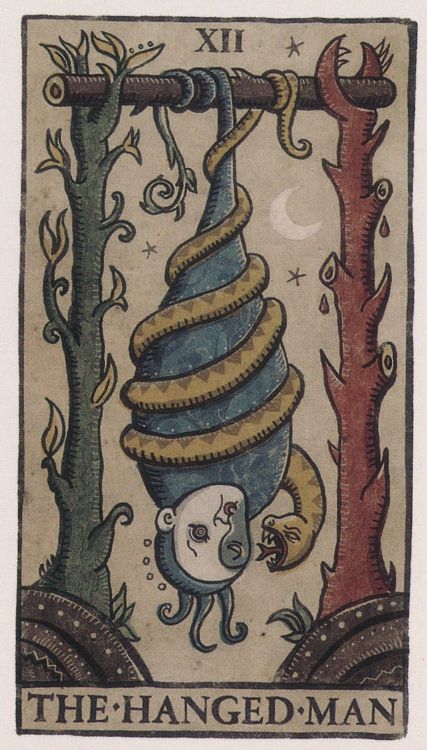

Here we have a man hanging from a beam. His body appears to be wrapped in a cocoon, like a butterfly chrysalis. A snake has coiled around his body and threatens to bite him.

This raises two interesting interpretations:

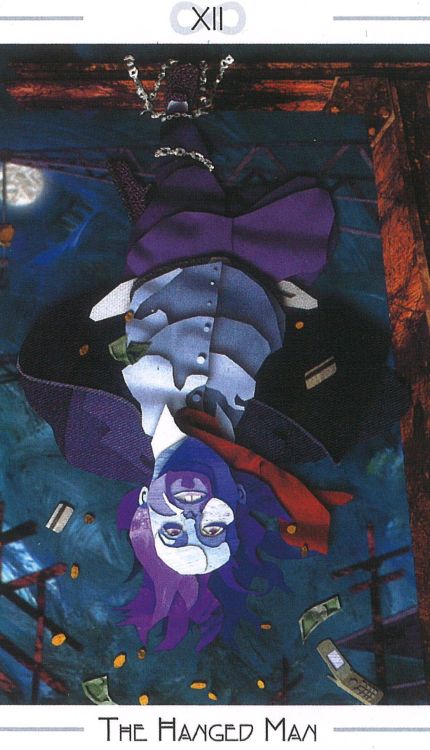

In this version, we see a man hanging from a steel beam, probably in a building under construction. He wears very urban clothing and, upside down, lets objects fall from his pockets, such as a mobile phone, banknotes, coins, and credit cards.

Here, the interpretation suggests:

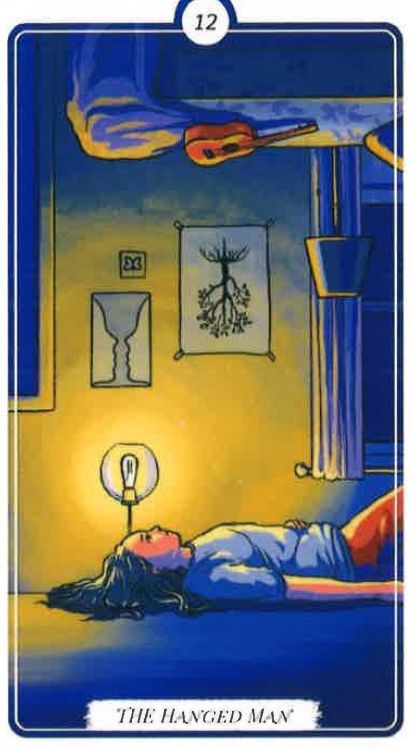

This card offers an inverted vision of The Hanged Man. We see a young woman lying not on her bed, but on the ceiling of her room. Above her (which is actually the floor), we find her bed and a guitar.

Notable visual elements include:

Here, the interpretation could be:

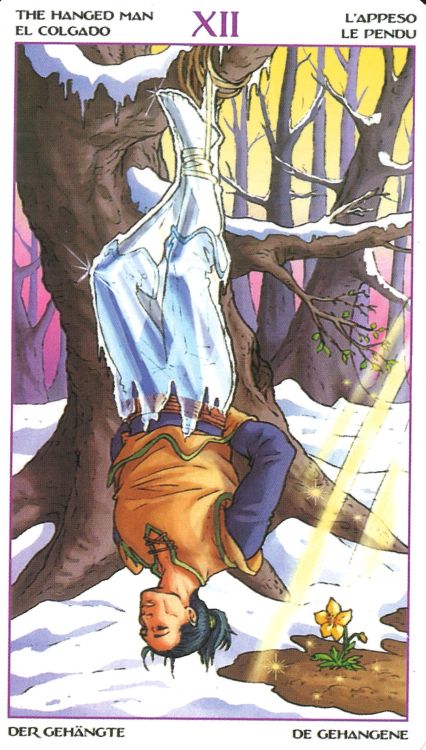

In this version, The Hanged Man is suspended from a tree in the middle of a winter forest, and his legs are completely trapped in ice. At the base of the tree, a golden flower is illuminated by a ray of light.

The key elements of this card are:

This version of The Hanged Man invites us to reflect on the difference between being held back by external forces and being frozen by our own inner blockages.

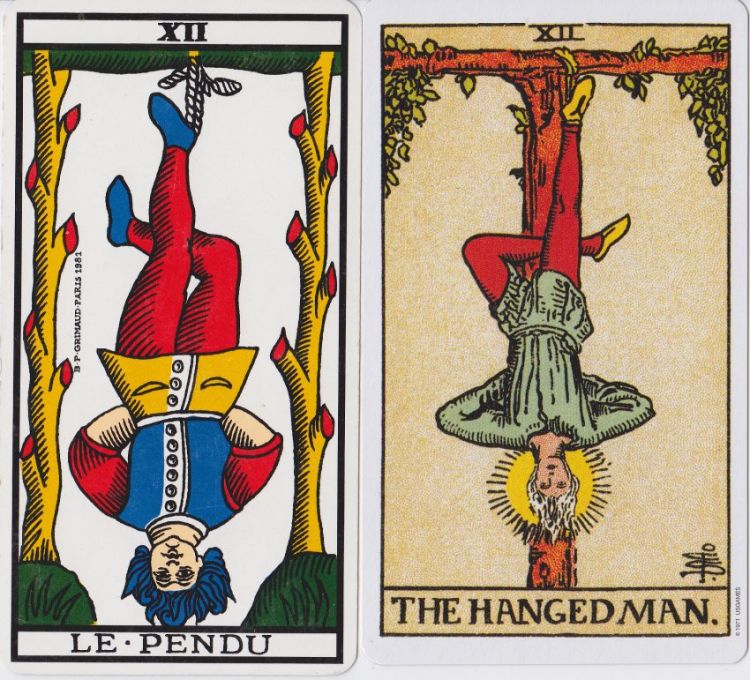

Key words for the 78 cards for the Tarot of Marseille and the Rider-Waite-Smith, to slip into your favorite deck. Your leaflets always with you, at hand, to guide you in your readings. Thanks to them, your interpretations gain in richness and subtlety.

It is essential to completely rethink the interpretation of the Hanged Man card. Rather than seeing it as a figure of punishment or suffering, we must deeply analyze what this image truly represents.

We see a man hanging, completely surrounded by the beams and the structure supporting him. This position can be compared to that of a fetus still in the womb. The beam could symbolize the placenta, while the rope echoes the umbilical cord. In this reading, the Hanged Man would represent a being in gestation, about to be born.

The fact that he is upside down reinforces this idea, as this is how a baby presents just before birth. This symbolism invites us to see the card as a sign of transformation and preparation for a new phase of life.

Another key element is the posture of his legs. He forms the number four with them, a symbol of stability and construction. This suggests that the Hanged Man is in a comfortable position that he fully accepts. Rather than an image of suffering, he seems to be in full acceptance of his situation.

An intriguing detail in the Type I Tarot de Marseille is that the character sticks out his tongue. This may mean that he is amused by the situation or expressing a certain carefree attitude, as if playing with his own destiny. Finally, in some depictions, he even appears to have wings on his back, which could indicate that he is ready to take flight into a new existence.

Thus, the Hanged Man card should not be seen solely as a symbol of constraint or immobility, but rather as a state of transition, a phase of waiting before a rebirth.

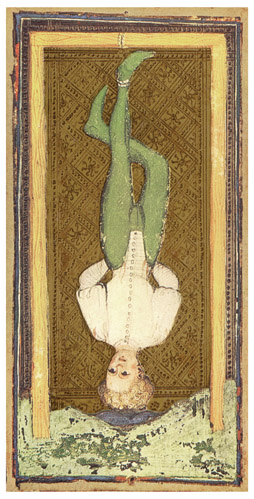

| Symbolic interpretation | Right direction (Positive) | Surpassing, Reversal, Questioning, Waiting, Listening, Surrender, Renunciation, Vision, Observation, Redemption, Faith, Prayer, Sublimation, Spirituality, Rest period, Non-action | Reverse direction (Negative) | Attachment, Deadlock, Resignation, Surrender, Letting go, Limitation, Blockage, Suffocation, Enslavement, Escape, Utopia, Illusion |

| Psychological interpretation | Right direction (Positive) | Receptive, Available, Intuitive, Devoted, Repentant | Reverse direction (Negative) | Passive, Resigned, Vulnerable, Easily influenced, Powerless, Dependent, Shackled, Impatient |

| Advice | |

| Do not act, this is not the time. Observe and meditate. Like the chrysalis, transform yourself from within. Discipline your mind for this | |

| Thematic Interpretation | Love | Devotion to the partner. Love sacrifice. Paralyzing shyness. Need for personal intimacy | Work | Chained to a job. Unemployment. Abandoning a position. Skills assessment | Money | Suspended or unprofitable business. Waiting before financial release | Family / Friendships | Brotherly bonds. Emotional dependence. Questioning family relationships. Emotional distance | Health | Fatigue. Weariness. Addiction. Feeling of being trapped. Need to go out and get fresh air. Emotional confusion. Refusal of care |

| Divination / Prediction | Who ? | A motionless or frozen person. A prisoner. An individual under constraint | Where ? | In prison. Held in a place. Where ties are strongest | When ? | At the time of assessment. When the pressure is too strong. To trigger a release | How ? | By surrendering. By questioning oneself. By looking differently. By letting events come to you |

Copyright © TarotQuest.fr