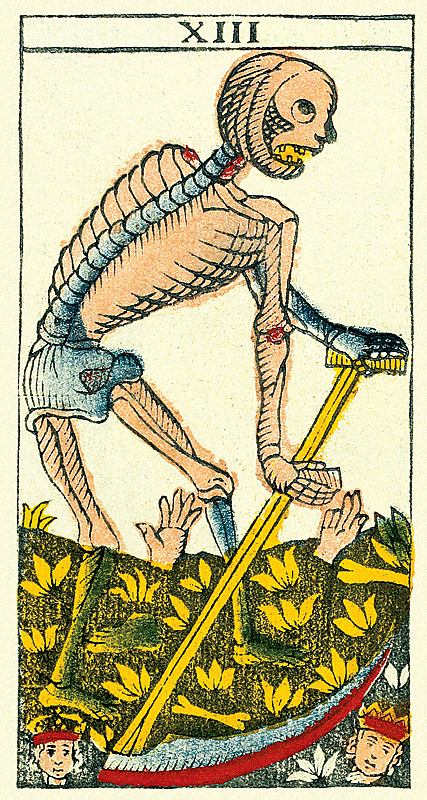

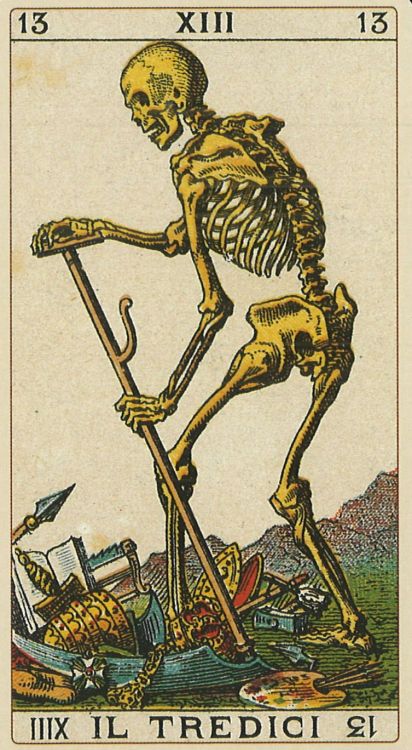

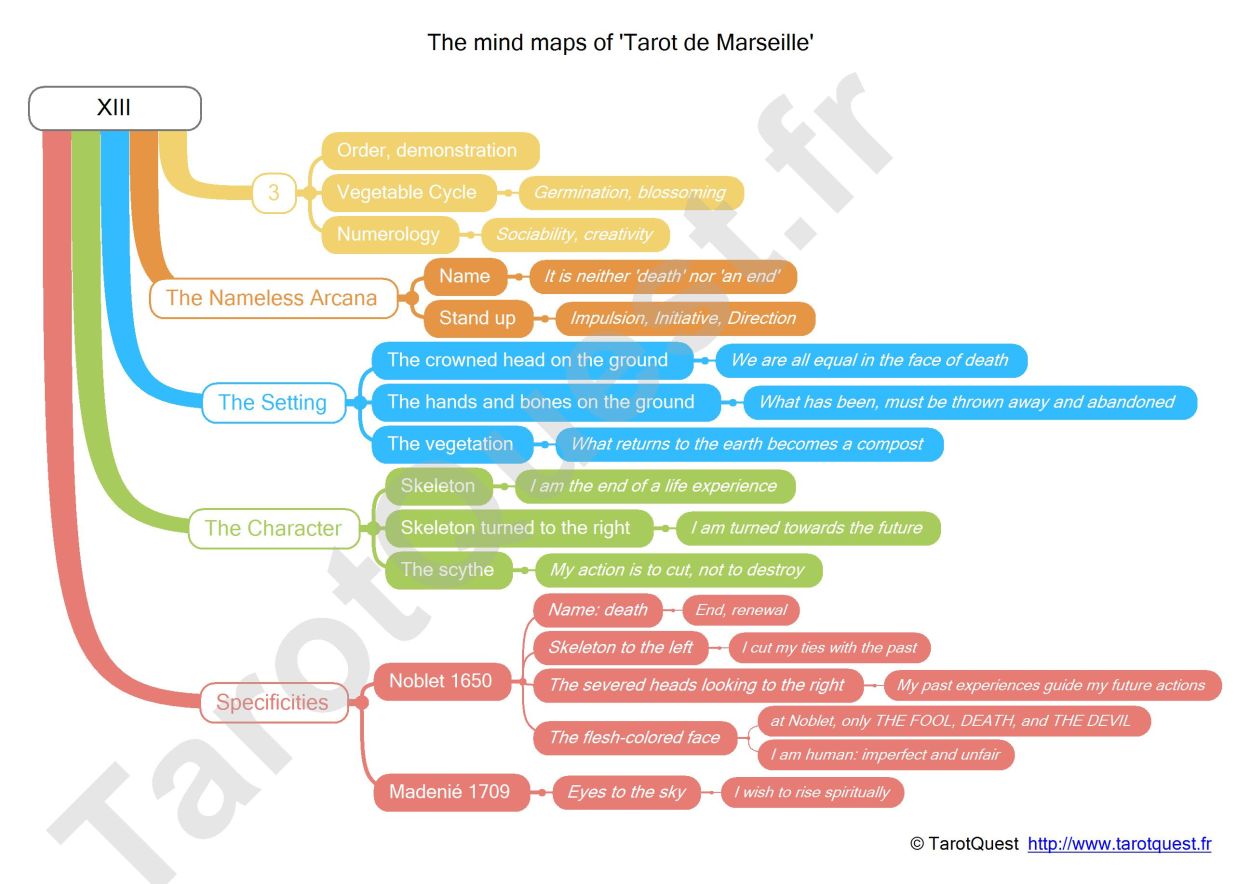

Among the twenty-two major arcana of the Tarot de Marseille, card XIII is undoubtedly one of the most intriguing and feared. Unlike other arcana, it does not bear an explicit name: only its number, the figure XIII, is inscribed at the top of the card. This absence of a name has fueled much speculation about its meaning and role in tarot iconography. However, its image is unmistakable: a skeleton armed with a scythe, advancing over a ground littered with severed human limbs. This depiction, rich in symbolism, finds its roots in medieval and Renaissance imagination, where death held a central place in thought and art.

The iconography of this card did not emerge from nowhere. It is part of an ancient artistic and spiritual tradition that has shaped the perception of death since the Middle Ages. During this period, the frescoes of the Danse Macabre, the engravings of the "Triumph of Death," and the transi sculptures (emaciated corpses depicted on tombs) reminded everyone of the inescapability of the end. This obsession with death, fueled by plagues and wars, is reflected in visual arts through both realistic and allegorical representations of the Grim Reaper.

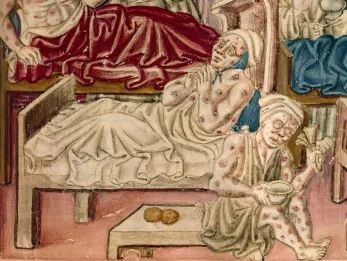

From the 14th century onwards, the representation of death became more pronounced with the emergence of the Grim Reaper figure. This nickname, referring to Death due to its noseless face, reflects how collective imagination personifies this inevitable passage. Under the influence of major epidemics, notably the Black Plague that ravaged Europe, death ceased to be an abstraction and became a visible, omnipresent figure in medieval iconography.

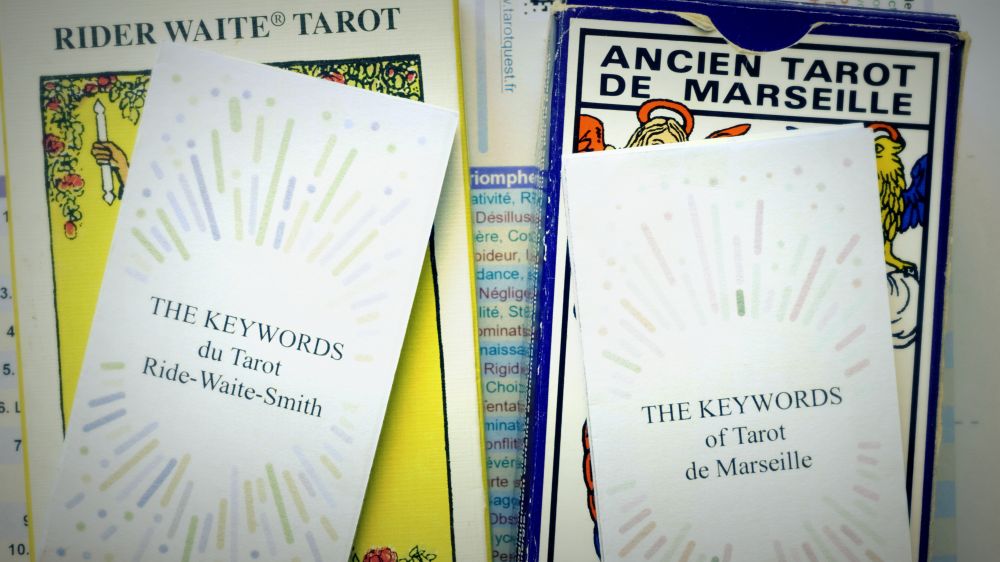

Artists of this period often depicted the Grim Reaper as an animated skeleton, a choice that conveyed the anxiety of the living in the face of fate. It appeared in sculptures, illuminated manuscripts, and engravings, wielding a scythe or a bow, symbolizing its power to cut down lives indiscriminately. This imagery would have a lasting influence on the representation of Death in art and, later, in the Tarot.

The "Triumph of Death" is a major artistic theme that flourished at the end of the Middle Ages. Many frescoes, particularly in Italy and Spain, depict a triumphant Death asserting its dominance over all, whether rich or poor, powerful or wretched. These works strike with their visual intensity and universal message: death is inevitable and touches every human being.

Among the most remarkable frescoes is the one in the Camposanto of Pisa, created in the 14th century. It presents a striking scene where decomposing corpses stand alongside carefree living figures, reminding us of life's fragility. Other representations, such as those in Palermo or Clusone, emphasize the concept of "memento mori," a constant reminder that life is fleeting.

These frescoes profoundly influenced Western iconography, particularly in engravings and playing cards. Their impact is evident in card XIII of the Tarot de Marseille, where Death, often depicted as a skeleton with a scythe, appears to harvest souls just as in these medieval artworks.

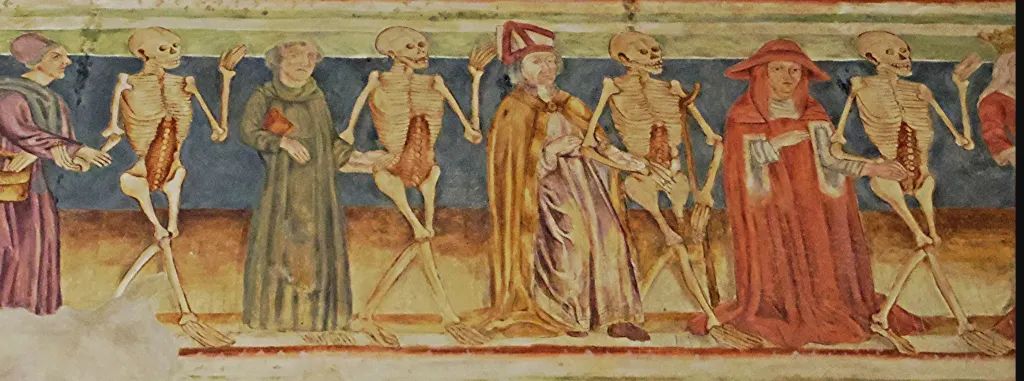

The Dance of Death is an artistic theme that emerged in the late Middle Ages, particularly in Western Europe. It depicts a procession of characters from different social classes – kings, priests, merchants, peasants – led by skeletons in a macabre dance. This scene illustrates the equality of all in the face of death.

Among the most famous frescoes is that of Bernotte Nottke in Germany, a striking work featuring figures of medieval society guided by death. In Paris, another Dance of Death fresco adorned the walls of the Cemetery of the Innocents in the 15th century, offering passersby a powerful vision of humanity’s shared fate. One could read: "You who live, it is certain that even if you delay, you will dance."

At the same time, the Ars moriendi, or "The Art of Dying Well," are texts that explain how to prepare spiritually for death. These works contribute to shaping an imagery where Death is an inevitable stage of the human journey.

The message conveyed by the Dance of Death is above all moral and universal. These depictions remind us that no matter one's social position or accumulated wealth, no one escapes death. They serve as a warning about the vanity of human ambitions and the importance of living with humility.

This theme fits into a context where plague and wars made death omnipresent in people’s daily lives. The artists of the time used the Dance of Death to raise awareness of the fragility of existence and invite viewers to reflect on their own destiny.

At the end of the Middle Ages, Europe was marked by a true obsession with death, fueled by tragic events such as the Black Plague. This epidemic, which ravaged the continent in the 14th century, wiped out a large portion of the population and left a deep imprint on the collective imagination.

In response to this catastrophe, medieval art and culture developed a strong taste for the macabre. Decaying corpses became a recurring motif, serving as a reminder of the fragility of human existence and the inevitability of death. This fascination with decay appears in sculptures, frescoes, and texts of the time, where bodies in decomposition are described with striking realism.

In medieval imagination, a person was not considered truly dead until their body had completely decomposed and only dry bones remained. Until then, interaction with the living was still possible according to some popular beliefs. The best way to ensure the final rest of a troublesome deceased was to burn their body until only dry bones and ashes remained.

Aristocrats, Church dignitaries, and elites sought to maintain a mystical aura that distinguished them from the common people. But the Black Plague changed this perception: it demonstrated that kings, bishops, and princes were just as vulnerable as peasants, falling victim to the same buboes and infected sores. This realization was reflected in 15th-century art, where representations of Death striking all social classes, from emperors to simple artisans, became very popular.

Illuminated manuscripts from the Middle Ages also reflect this obsession with death. They contain scenes illustrating dancing skeletons, tormented souls, or bodies in an advanced state of decomposition. These depictions are not just artistic; they also carry moral and religious significance.

Among the most notable works are the "Books of Hours," which often include images of death as a meditation on the vanity of earthly pleasures. The "Memento Mori," on the other hand, constantly remind readers that life is fleeting and that everyone must prepare for the afterlife.

Over time, depictions of decomposing corpses were replaced by anonymous skeletons. The Church, seeking to counter superstitious beliefs, reinforced its doctrine: at death, the soul leaves the body permanently with no hope of return. Thus, ghosts, animated skeletons, and other apparitions were assimilated to demonic manifestations.

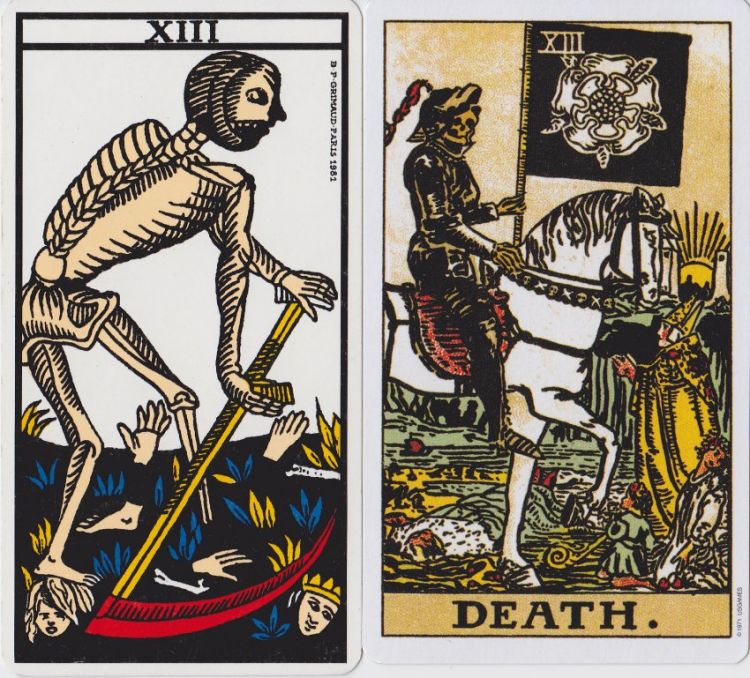

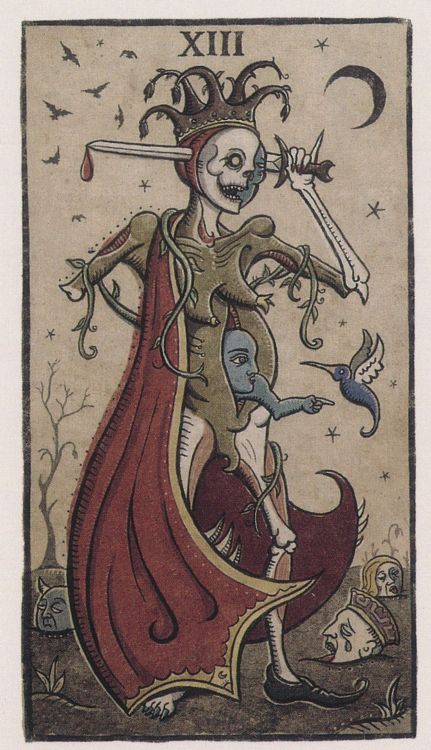

In this tarot, Death is depicted as a skeleton, a figure already well established in the iconography of the time. The inspiration comes directly from the dance of death and frescoes of the "Triumph of Death" that circulated in Italy and throughout Europe. This visual influence reinforces the idea of an inescapable cycle of life and death.

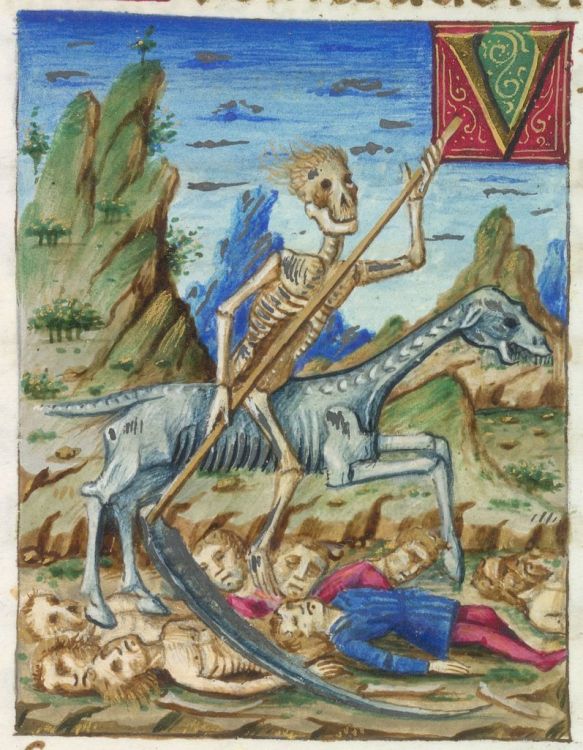

Other ancient decks, such as the Charles VI tarot and the Rosenwald sheet, also feature striking representations of the Death card. These versions, although different in their artistic styles, retain the same fundamental symbols: a skeleton armed with a scythe, riding a horse, often accompanied by corpses or human fragments.

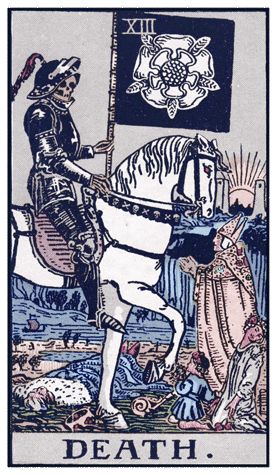

Its iconography is partly inspired by the Bible, notably the Book of Revelation (Chapter 6, Verse 8): "I looked, and there before me was a pale horse! Its rider was named Death, and Hades was following close behind him."

The Death card in the Charles VI Tarot merges this image with both the rider of the Apocalypse and the figure of the Grim Reaper, harvesting souls from all social ranks with his scythe. A simplified version of this theme appears in the Rosenwald Tarot. In contrast, in the Bologna Tarot, some of these iconographies were preserved, while in most tarot decks outside Italy, the mounted Death figure gradually disappeared until its reappearance in the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot in 1909.

These early Death cards thus demonstrate continuity in the representation of this theme, drawing directly from the art and beliefs of their time. They lay the foundations for the iconography that would be preserved and reinterpreted in the Marseille Tarot and modern versions of the tarot.

While the earliest representations of the Death card in historical tarots were often highly detailed, featuring expressive skeletons and macabre scenes, the image was gradually simplified. Several reasons may explain this evolution:

In the early historical tarot versions, including the Charles VI Tarot, the Rosenwald Tarot, and the Visconti-Sforza cards, the iconography of the Death card was already relatively well established. The image of Death appeared fixed, with recurring elements such as the skeleton and the scythe.

However, there is one notable difference between these early representations and those in the Marseille Tarot. In early historical tarots, Death was often depicted on horseback, evoking the imagery of the medieval Grim Reaper. With the appearance of the Marseille Tarot, Death is now depicted on foot.

Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France, the period when the Marseille Tarot took its definitive form, was marked by a more humanized vision of death, breaking away from medieval imagery. The horse was often associated with nobility and war, and its removal could reflect a desire to make Death more universal and closer to ordinary people. This also aligns with a broader trend of the time to move away from overly apocalyptic imagery deemed too religious or frightening.

A Death on foot fits more into a process of evolution and natural change, unlike a mounted Death, which evokes a sudden and violent assault. The horse can be seen as a symbol of speed and conquest. By removing it, card XIII emphasizes inner transformation and a gradual change.

In the Marseille Tarot, card XIII has a unique characteristic: it does not bear a title. Unlike the other Trumps, which clearly display their name at the top or bottom of the card, this one remains anonymous. This absence of a title is not an oversight but a deliberate choice that raises several questions.

Several hypotheses explain this particularity:

This lack of a title turns the card into a mysterious entity, often called "the Nameless Arcana" by cartomancers. This term suggests an inevitable and impersonal force, an energy of change that goes beyond the simple notion of an ending.

In hermetic and esoteric traditions, leaving something unnamed gives it additional power. In occultism, hiding or making a name unpronounceable enhances its mystery and influence.

By refusing to explicitly name it, the Marseille Tarot encourages us to grasp this card beyond our fears and fully embrace the concept of transformation.

From the Tarot of Pierre Madenié (1709), we observe a shift in the representation of the Death card. In Type II tarots, Death is now oriented to the right.

This iconographic modification can be interpreted as a change in symbolic perspective. In Type I, Death reaps the past and emphasizes the necessity of breaking away. In Type II, its orientation to the right brings it closer to a symbol of renewal and transformation. By looking towards the future, the card highlights rebirth rather than the end itself.

We can distinguish two main interpretations:

This directional change highlights how the Tarot of Marseille has evolved over time, reflecting different conceptions of passage and change. While the Middle Ages and the Renaissance were marked by a more fatalistic view of death, the Type II TdM incorporates a more dynamic and future-oriented dimension.

Unlike the classic versions showing severed hands and heads, this card features various symbolic objects and accessories representing human activity.

We can observe several symbols of power and authority:

The card also presents symbols of work and creation:

Death, facing left, indicates that all these elements are doomed to disappear. However, this ending is not necessarily negative. It can represent a necessary transformation, a renewal. The main message is not so much about the equality of all before death but rather the fleeting nature of all human creation and activity. If everything made by man can be undone, it is also what allows for change and evolution. Every creation, every power, every war, every knowledge, and every art comes to an end, opening the way for new possibilities.

In the 18th century, with the popularization of cartomancy books, the perception of death as transformation rather than an absolute end became firmly established. The cartomancy books of Etteilla significantly influenced the interpretation of the cards. Although some suggest he may have relied on a now-lost oral tradition, his particularly negative interpretation of the Death card remains unique.

Etteilla associated this card with:

However, this pessimistic view was not widely adopted. Interpreters of the Tarot of Marseille agree that Death symbolizes the natural end of a cycle. The reduction to a skeletal state suggests the elimination of the superfluous, carrying the promise of renewal. French occultists like Éliphas Lévi and Oswald Wirth retained the traditional imagery of the Tarot of Marseille while reinforcing the theme of transformation.

These occultists claim that death promotes life by eliminating what is obsolete, thus allowing the emergence of new possibilities. The heads and hands emerging from the ground symbolize the persistence of our ideas and actions beyond our physical existence.

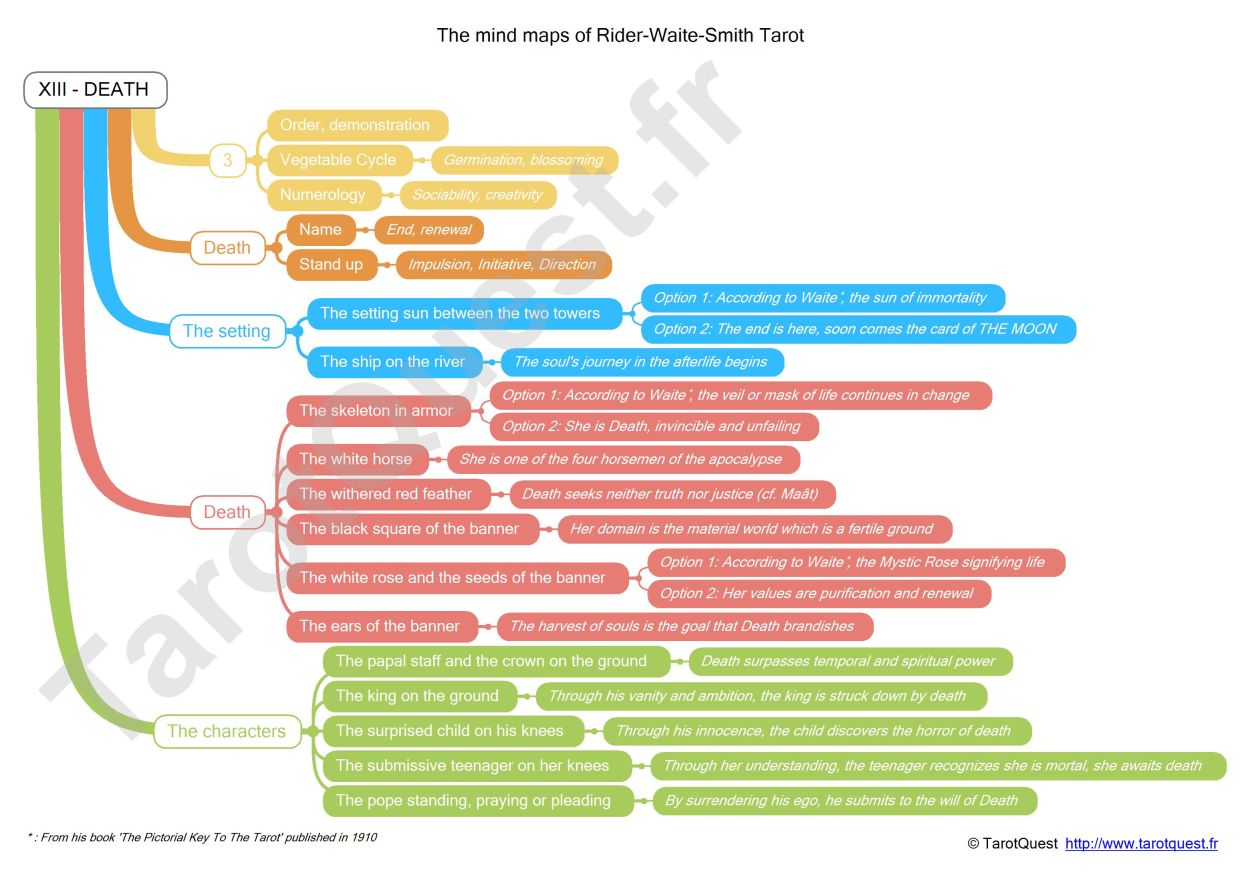

The Death card in the Rider-Waite-Smith tarot, published in 1910, is inspired by medieval iconography, depicting Death on horseback trampling various figures :

Waite distinguishes between the Hanged Man, representing mystical death, and this card, symbolizing physical death. The card is rich in Rosicrucian, Freemason, and Templar symbolism, particularly with the white rose on the flag. The New Jerusalem, standing out against the rising sun, symbolizes the promise of eternal life. The stream, reminiscent of the one from the Garden of Eden, represents the eternal cycle of energy: evaporation, cloud formation, rain, and flow.

Interestingly, the armored skeleton is inspired by an engraving by the famous German artist Albrecht Dürer. In a modern reading, this card can also symbolize deep personal transformations, career changes, or the end of a phase in life.

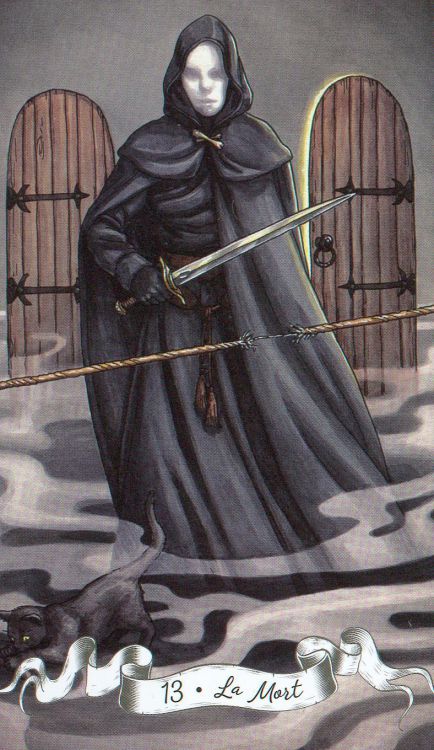

This contemporary tarot, specially created for practitioners of Wicca and modern witchcraft, presents a version of Death that is particularly faithful to the symbolism of the Tarot de Marseille. The card features a mysterious figure clad in a long black cloak and wearing a white mask, with eyes that are not even visible, creating a total anonymity effect.

The main symbolic elements of the card are:

The symbolism of this card is rich in meaning:

It is particularly interesting to note that one of the doors is slightly open with its handle visible and lets light through, while the other remains tightly shut. This difference may suggest that some choices are already predetermined or that some options are naturally more accessible than others.

The white mask worn by the figure reinforces the universal and impersonal aspect of death, emphasizing that all human beings are equal before it, regardless of their social status. In a modern reading, this card can symbolize:

This version of the tarot, with its feminist and modern approach to spirituality, reminds us that death is not always to be feared but can be seen as an ally in our process of personal transformation.

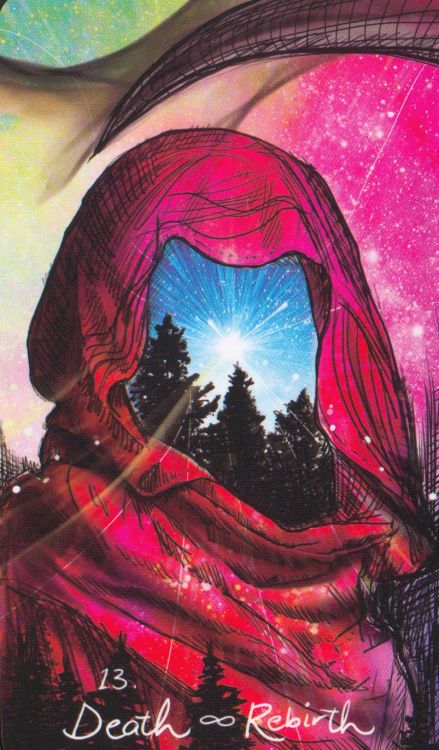

This contemporary tarot, created by Chris-Anne in 2019, offers a modern and spiritual vision of the traditional arcana. The Death card, named here "Death and Rebirth," presents a unique and profound interpretation of the theme of transformation.

The main visual elements of the card are:

This unusual representation offers several levels of meaning:

This card invites us to consider death not as an end but as an integral part of the natural cycle. The presence of the landscape in place of the face may suggest that death allows us to "explore" humanity and our own deep nature. It reminds us of our intimate connection with natural cycles and our innate ability to renew ourselves.

The fir trees and natural setting may indeed evoke an ecological dimension, but they also represent:

This modern interpretation of Death moves away from traditional macabre representations to emphasize the transformative and regenerative potential of profound change. It reminds us that every ending carries within it the seeds of a new beginning, symbolized by this radiant star shining at the very core of our being.

This version of the Death card presents a powerful and complex image, centered on a female figure that is both living and skeletal. This duality immediately evokes the process of transformation and the life-death-rebirth cycle.

The main elements of the card are:

The symbolism is particularly rich:

This card perfectly illustrates the concept of death-rebirth without needing to explicitly state it in its title, unlike the Light Seer's Tarot. The transformation is represented in a visceral and organic way, reminiscent of the alchemical processes of dissolution and recomposition.

The crescent moon adds a cyclical dimension to the whole, reminding us that death and rebirth are part of a natural and perpetual cycle. This card teaches us that sometimes, it is through a conscious sacrifice of what must die within us that something new and precious can be born.

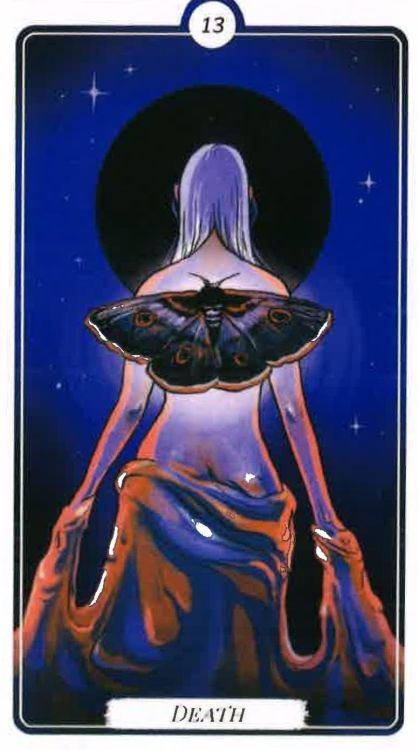

This modern interpretation of Death presents a striking image centered on a young woman seen from behind. This feminine representation offers a unique perspective on the themes of transformation and letting go.

The main visual elements are:

This card offers several levels of symbolic interpretation:

1. The Journey into the UnknownThe woman faces a black disk, suggesting:

The nocturnal butterfly evokes:

The ambiguity of the material covering the woman suggests two interpretations:

This card also speaks to:

This version of Death moves away from traditional macabre depictions to offer a more initiatory vision. It evokes a rite of passage where symbolic death allows for spiritual rebirth. The feminine figure embodying this process recalls ancient goddesses of transformation like Persephone or Inanna.

In divinatory reading, this card may suggest a moment of deep transition, a need to let go, or an invitation to shed superficial layers of our personality to access our true essence.

Key words for the 78 cards for the Tarot of Marseille and the Rider-Waite-Smith, to slip into your favorite deck. Your leaflets always with you, at hand, to guide you in your readings. Thanks to them, your interpretations gain in richness and subtlety.

The Death card primarily represents a process of detachment, rather than just an ending or transformation. It fits into the logical sequence of the initiatory journey of the Tarot de Marseille, the famous 'Fool's Journey'.

Strength (XI) first teaches us the mastery of our inner bonds. The woman and the lion symbolize our ability to tame our impulses while maintaining harmonious connections with our deep nature. These bonds, while necessary, must be balanced.

The Hanged Man (XII) then invites us to observe these bonds from a different perspective. Whether it is social, emotional attachments, or the symbiotic maternal bond (represented by the umbilical cord), this card encourages us to become aware of our dependencies.

This is where Death (XIII) intervenes, not as an end, but as an opportunity to consciously free ourselves from these ties. It represents the voluntary act of cutting what holds us back, limits us, or prevents us from evolving.

After the detachment brought by Death, Temperance (XIV) offers a balanced reconstruction of bonds. It suggests relationships based on mutual exchange, where each person gives and receives equitably. It is the learning of healthy interdependence, as opposed to dependence.

However, the Devil (XV) warns us: if the ego has not truly been abandoned during Death's passage, we risk falling into the opposite extreme. Instead of giving everything without receiving anything, we might shift into total selfishness, seeking to receive everything without giving anything.

This sequence shows us that Death is not so much about transformation as it is about a conscious act of liberation. It does not necessarily promise rebirth or renewal but offers the possibility of letting go of what no longer serves us.

In modern psychology, this card represents:

- The ability to let go of toxic attachments - The art of detachment as a path to freedom - Accepting the end of cycles without necessarily anticipating what follows - Freeing ourselves from conditioning and limiting patterns

Thus, Death invites us to exercise our most fundamental freedom: the ability to say "no" and detach, without the obligation to rebuild immediately. It is in this space of emptiness and freedom that its true power lies.

| Symbolic interpretation | Right direction (Positive) | End of cycle, symbolic death, conclusion, change of level, point of no return, transition, passage, rebirth, revolution, rectification, stripping away, liberation | Reverse direction (Negative) | Disillusion, pain, endless regret, resistance to change, bound by the past, vicious circle, loss, danger |

| Psychological interpretation | Right direction (Positive) | Detached, brave, renovator | Reverse direction (Negative) | Repeat offender, neurotic, powerless, fatalistic, fearful |

| Advice | |

| Accept that everything has an end. Resolve or cut ties with the past. Let go of your illusions. Abandon what needs to be left behind. Express your inner strength. Transcend your nature. Renew yourself. Create something new. Be brave. Time for a clean sweep! | |

| Thematic Interpretation | Love | End of being single. Relationship transformation. Breakup. Divorce. Winning back an ex-partner | Work | Career change to a different activity. Radical change in mission. End of partnership. Contract termination. Dismissal | Money | Looking for different income. Change in investments. Considerable losses. Fear of recapitalization | Family / Friendships | Departure of a loved one. Family 'issues'. Long-lasting disagreement. Unaccepted separation | Health | Radical and transformative decision (sports, no alcohol, vegan, etc.). Deep fears or neuroses. Disease Recurrence |

| Divination / Prediction | Who ? | A person making decisions for themselves. A surgeon. A police officer. A bailiff | Where ? | At the new home. In the new company. At the hospital. At the cemetery | When ? | End of an evolution cycle. A move. A break in routine. A physical or emotional mourning. A medical operation | How ? | By changing lifestyle. By doing things differently. By speaking differently. By working differently |

Copyright © TarotQuest.fr